Autobiography Book 1

July 4, 1936

Foreword

I am sitting under a Linden tree on the Vassar Campus on the evening of my 55th birthday. I selected this spot to begin the opening chapter of the history of my life. The bees are droning musically as they flit to and fro from fragrant buds and blossoms. The evening is sunlit cool and peaceful. A mild breeze gently sways the branches. The ground beneath the trees is dappled with alternate sunlight and shadow. The situation typifies in a make believe fashion just the very things for which I have striven for over forty years though I am far from the realities in actual fact. The old man does not sit under the Linden at peace pleasantly reminiscing near the end of a long road of life wherein he sipped the nectar of honey coated years. Neither does an embittered old fellow sourly chew the acid cud of disappointment and frustration. Instead there sits a defeated old man left cold and emotionless by the harsh treatment of the years, yet quietly and without ostentation, drama or heroics holding fast to his ideas principles and ambitions and determined to fight for them to the end in the teeth of futility less through courage than through a dogged thick headed dullness estopping that shift of ideas necessary to adjust older generation minds to the modern and somewhat reverse modes of thought. By reverse modes of thought “I am not implying property or general condemnation of all modern ideas. With many of these I am wholly in accord, discerning in them the essence of age old altruistic principles.

I belong to probably the last generation which school readers and popular fiction and news press and pulpit professional patriots and sociologists can sell such ideas as: Thrift honesty and personal integrity pay best. Virtue eventually triumphs. Our wars are holy, our soldiers noble fellows, displaying innate heroism. To die for one’s country is a glory transcended only by dying for one’s religion. Those who save in youth reap the harvest of happiness, comfort and independence in their old age. Interest in and close application to one’s work results in promotion. All once to a great extent true, but in our day seems quite fallacious.

Today, only dumb clucks save. Spend your money while it’s worth something (i.e. before inflation comes). Let the government support you when you are old and long before it. Principles are old fashioned church engineered handicaps that make the honest minded and conscientious a pushover for the wise guys. Close application to and interest in ones work betrays a fear of losing one’s job and implies a lack of other resources. It’s a please don’t hit me attitude according to the physiological deductions of modern wise guys. As to war, “What me fight?” I ain’t mad at anybody! Let the munition makers and other millionaires and statesmen fight. If they need any help, let them roundup a lot of these grey haired so and sos. Keep us young fellows to breed from. “The women gotta be looked after you know.” Is often the tone and gist of many voicings of modern sophisticated youth. As to religion: “Oh yeah, I’ve been in a church once. They preach and pray in there. Yup! I am a pious son of a this and that.

I am not condemning the youth of today. My own and previous generations were so chuck ablock hypocrisies, injustice, hardship and cruelties that it makes this latter day sophistication and contempt of heretofore sacred principles and ideals seem like poetic justice. Eventually I believe, the world in general and America in particular will strike some sane balance between radical, conservative, and reactionary thought that will be generally satisfying and conducive to peace.

I am considered a strange man. My behaviorism has been often under fore. It never seems to suit anybody no matter how many adjustments I made with the objective of pleasing them. Many like me first rate until I dare to say the truth. They then screech for my hearts blood. I am either a garrulous little windbag or a sour shut mouthed rat. A wise cracking smart-aleck or a poker faced criminal looking enigma. One who registers every emotion in face and eyes or a vacant staring unemotional question mark as blank as an imbecile. The element of personality of course enters here. This I have proven by using some good looking formidably muscled fellow to make wise cracks of my own coinage. They go over big and are laughed at uproariously by all and accepted good naturedly by those who’s hides they sear except for an ugly look in my direction, often accompanied by the enquiry, “What the hell are you laughing at you old this and that?”

Of known thrift and suspected the possessor of money designing women have frequently encouraged me to offer myself a victim to their mercenary objectives. I clicked several such traps, and had as many narrow escapes. Shifts of environment and the grace of God saved me from others. A later in life caution, very hard work, and various interests diverted me from sex interest beyond an artistic and poetic admiration for the charms of the fair sex. I am consequently and fortunately a bachelor. Fortunately I say because I am not the type of a man to whom a woman could be loyal. I never was sexually vigorous, socially inclined, well dressed or physically attractive. Round shouldered, flat chested, stooping, bowlegged, small in stature (5ft 5in), red faced, scowling, long nosed, and until 45 years of age, never weighed more than 120 pounds. Most of the women and girls that I handled were as big as myself and some were larger. I always strongly desired contact with small doll like women, but due to my own smallness, I dreaded to breed with them. In the company of little women I always felt manlier than at any other time. In associations with heavier built women, I felt inferior, and was more often absorbed in calculations as to the numbers of children she could produce for me, than any other manifestation of regard. I think I can understand the point of view of the ancient despot of whom it was said that “He kept his big women for breeders, and his small ones for pleasure.” He was probably a little cuss with a big ego like myself.

I will seriously regret if any of these views so far, or later on expressed, offend the honest loyalties of anyone. I had loyalties myself once, and wish I had them still, or at least could maintain their illusions. I realize that maybe many readers of these lines may be the product of cultures which will at first glance indignantly resent much contained herein. This I regret but make no apologies. I write to please no one, not even myself. I am an old man. The world has rebuffed me. My self-respect has been challenged, my intelligence insulted. Were I to go to the grave without making some attempt to answer the challenge, vindicate my manhood, and explain my philosophy of life and those points of view which strong authority or a superior strength denied utterance otherwise; I would be lacking in sportsmanship and probably slip into oblivion with the poor voiceless slumbering meek, who in life solely due to the fineness of their gentile nature bore the burden and hardship of the world’s suffering and outrage while rascals, hypocrites and brutes claimed the land whilst chanting the beatitudes.

I denounce no worthwhile tradition, yet scorn the window dressing and illusions of many, and will fight from the grave if possible, the hypocrisies that lurk beneath them. I claim the right to live and prima facie concede the same right to every living soul, white, black, brown, red, or yellow. I respect the fundamentals of every culture promoting the general welfare. I tolerate cultures forced into being by the menace of enemy cultures. “One evil begets another” as my father used to say. I tolerate, aw what the hell, I’ve been too goddam tolerant, and so adjudged a coward. “We know you are bread” sneered a certain critic who shrieked for immunity and protection when reprisals were attempted.

Oh yes, I am a “clever bum” although I never drank and always worked hard. These left handed subtly implied compliments emanated from the representative of a culture I wish someday to visit (not of the local brand, but from that of an esteemed contemporary). I can and do laugh at that, and the one who made the remarks. I am myself a curious mixture. The product of some cultures, the lack of others, and the superimposed excess of others.

Looking back over more than fifty years I can scarcely reconcile the old fellow of today with the “me” of any of the five previous decades. There are connecting threads which the years wove together forming a character which in analysis my reveal the influences of heredity, environment, personality, besides many other things neither admired nor condoned. Believing that my life experiences and observations are worth recording I herewith present my autobiography.

It was April 1884. Little boy was having the time of his life. His baby sister had stopped crying and the funny chocking noise that both he and she used to make last week. He had stopped too, and the fat man with the valise had patted him on the head and said he was all right now. Something seemed the matted with the rest of the family though. All were crying except for him and his sister. She was asleep now and they were all crowded around her crying. Even his father cried. He didn’t think men cried. Will, who was 5 years old nudged him and said “Why don’t you cry Joe? The baby is dead”. Dead? What did that mean wondered Joe? They’ll put her in a hole in the ground sobbed Will. Joe knew better. His father wouldn’t let anybody do that to Katie, him or Bill, and Jim and John were big enough to run away.

The neighbors came in. Among them Mitty, and Old Mrs. Brown. Joe liked Mitty. She was Mr. Smith’s wife and they lived on the corner where the big tree was. Mrs. Brown was cranky, she used to scold mother and make swats after us children when we got noisy. All her children were great big men, some of them as grey haired as herself. She was about 80 years old father said. Others came also, Joe didn’t know them, but when they patted and kissed him he would dance until Will would come over and stop him whispering: “The baby is dead”. Finally, a white haired man came with two boxes and some ice. She didn’t cry at all. Two days afterwards a big white wagon came. They put Katie in it. We all got into another wagon and had a dandy ride though all the rest of them were crying but me. They then put the box Katie was in down in a big hole. Then I cried with the others.

Thus my very earliest recollection is associated with the death of one of my own family. Another is a vague remembrance of Brother Eddie’s birth later in the same year. There had been another brother of the same name who had died before I was born I learned later. I cannot associate much in my memory with the next few years until 1887 when four men who were killed in a quarry were given a single funeral by the old Knights of Labor of the village. It is claimed that a thousand men marched that day, something tremendously big for a small town like Rosendale. It is still bragged about by those who remember it.

The year 1888 is somewhat clearer in my memory. I recall the Binnewater strike in February of that year quite well. I was going to school and learned to shout with the other kids: “Binnewater, Blackleg, Scab” without realizing its purport or implications. Somewhere in between these two events there are three remembered incidents which obviously predate them. Burning my dress while mother was down at the store, and again tearfully shouting for her when Brother Eddie tumbled into a partially filled wash tub on the floor, while mother was out hanging up wet clothes on the line. The third is my first day at school. Brother Jim brought me up to the big boy’s room. There was a man teacher and what to me appeared to be grown men, which in many cases was correct. One or two of these sported a mustache. They all made a big fuss over me and vied with each other to have me sit with them.

Wildy Mack caught flies and stuck pins in their rear, then watched them drag the pins around. I didn’t like that. Muckle Stolls got me to sit with him awhile. Brother Jim came to get me. He and Muckle got into an argument that ended in a scuffle. The teacher, Robinson by name, ordered them out into the narrow hall where two staircases ran down from the landing. The classroom door was open and I saw the teacher holding a wide strap in his hand. “Hold your hand out Fleming” he commanded sharply. Just then Muckle dropped catlike on all fours behind the teacher and winked grinningly. Jim bucked the teacher Billy goat fashion in the stomach. There was a laud crash followed by roars of: “Good for you Red”! The infuriated Robinson started to reclimb the stairs. Muckle stood with a hand on each railing and as the teacher got in range, kicked him under the chin. I started to cry and one of the hooting howling laughing big fellows gathered me up and brought me to where Jim was. He brought me home and told mother there was no more school that day because Mr. Robinson had another bad spill in school today. Recalling this phrase nearly 50 years later after, I concluded that this learned pedagogy must have been subject to such bad spills with more than occasional frequency. Expulsions followed of course, but attendance laws being practically nonexistent; Jim played hooky until able to locate a job.

Local Memoranda

For purely local interest I here record the names of those I recall being present on that occasion:

Andrew (Dutchy) Smith – Smitty the barber’s son.

Lonnie Canfield – nephew of Old Lon.

Irving D. Rhodes – son of canal superintendent George Rhodes.

Brad Smith – son of Ed T. Smith quarry superintendent.

Jim “Red” Fleming – son of James Fleming Sr.

Frank “Muckle” Stolls – son of Jake the shoemaker.

Wildy Mack – the widow Mack’s son.

Gene Fields – later of Buffalo, Baltimore, and Pittsfield MA.

Peter A Lee (properly Barry) – who dissipated his grandfather’s fortune and died young in the almshouse.

Dart Snyder – son of AJ Snyder, the cement manufacturer.

Henry McQueery

Fred Schwarman

Poppo Freer

Jesse Brown – the butcher’s son. Lew Brown was a member of the Board of Education.

I met Jesse Brown the evening after making the foregoing entry in July 1936. I met him in an out of the way point on Vassar Campus. Neither of us recognized the other, but a reference to Ulster County developed that we were fellow Rosendalers. I had not seen him in 30 years.

January 1 1937

I recall the blizzard of 1888 quite well having several definite impressions of the occurrence. I remember how the house shook, the intensity of the cold, and a man moaning outside: “Oh I’ll die sure”! It was Pat Mc McCabe a horse trainer and farm hand for Matthew Quays (or Keys) Superintendent f the New York Cement Works. Father started out, but Old Pappy Lee had put a light in his window that directed the bewildered McCabe to the house and safety. The next morning the snow was higher than our yard fence and I saw a yoke of oxen breaking the road past our house.

About this time, romance first touched my life. We children used to get buttermilk for the family from Ed Smith who lived on what later became the Ackerman farm. Mr. Smith was superintendent of the works where father was employed. He had four daughters ranging from 15 to 25 years old. Helen Smith, a splendid looking woman of about 22 years used to make a great fuss over me. I took things very seriously and decided to marry her in spite of the great discrepancy in our ages. Announcement of my plans provided considerable merriment the occasion for which I could not understand. To me the situation was serious and in no sense a laughing matter. I was wholly innocent of sex knowledge and pulses. I wanted her because of the soothing hypnotic way she influenced me. I just wanted to curl up in her lap and just go to sleep.

Of 1889, I recall the Johnstown flood, Nellie Bly’s trip around the world, and discussions anent the Sullivan - Kilrain fight. About 1890 a parochial school opened in Rosendale. From then until 1894 I read all the histories and geographies I could get ahold of and ignored all else. During these years my plans for the future shifted vicariously. I considered the priesthood with a view of later becoming Pope, and eventually St. Joseph the Great. On the other hand, there was the death of Jessie James to be avenged, and the glamorous appeal of an outlaw’s life to be considered. I liked pugilism too and as for money, Pshaw! I’d just make a million or two when I got around to it; the details and procedures seemed non-essential. I’d just make the money, that’s all.

In 1891 my brother Eddie died. It was on a May evening (the 17th), a neighborhood boy wanted me to accompany him downtown. Brother Bill protested against my going, I ignored his objection and when I came back Eddie was dead. I never forgot that and nowadays take more stock in what Bill says than I do of all others put together. Brother Bill is less than two years older than myself and seems nearer to me than all the rest of the family. Although we have but few tastes in common, he is quiet, sober, humorless, businesslike, and all for his people. He rarely reads more than the newspaper headlines, and is a good businessman with a faculty for figures and hard work.

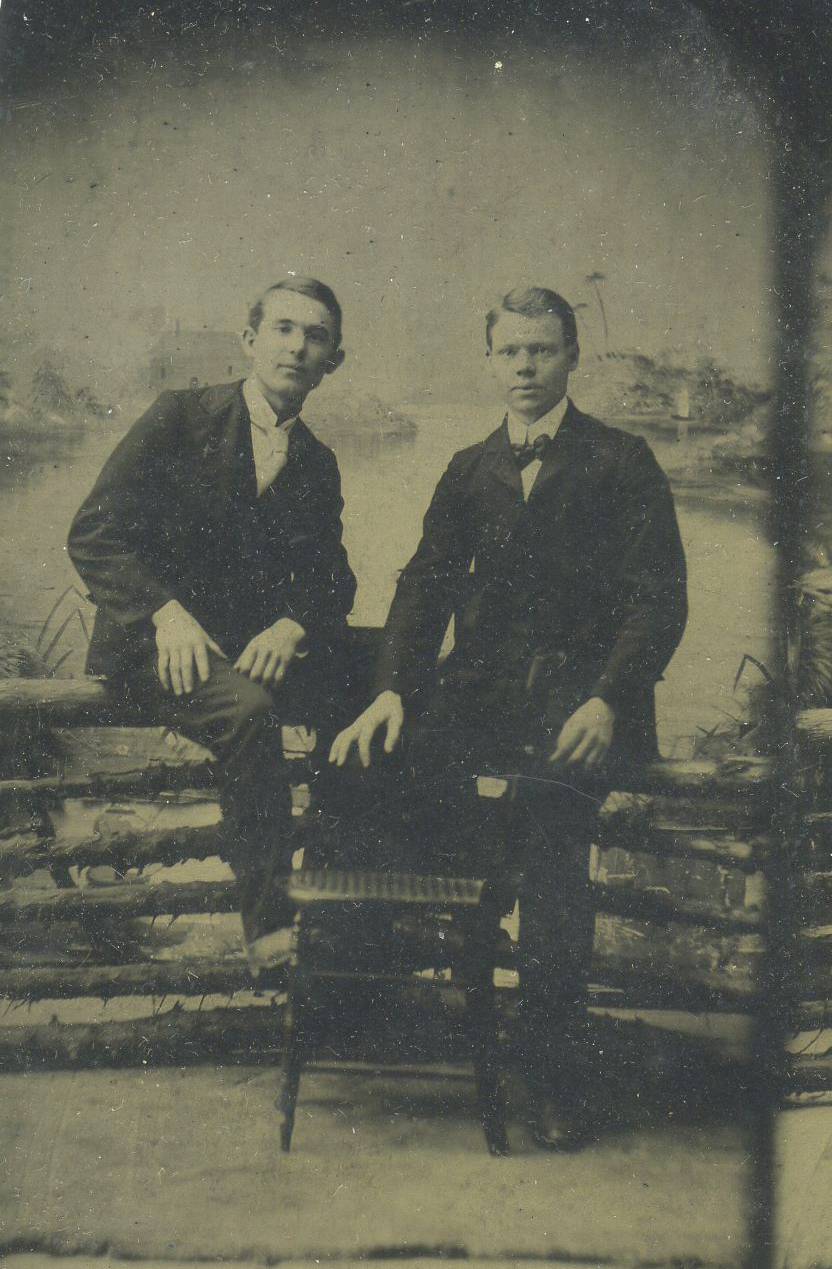

On the other hand, I am an avid reader, an incessant scribbler, a wise cracking smart-aleck garrulous, temperamental, interested in almost anything, and think everyone else should be also. I am learning of late however, to keep my mouth shut and use my pencil more. Brother Bill is the only one of the family that lacks an acquaintance with a few classics or a smattering knowledge of science and philosophy, yet he has the best head and heart of them all. His interest in us is sincere, kindly, and unselfish. He is a big heavy set man. I until past 45 rarely exceeded 118 or120 pounds. I am small, frail, and stoop shouldered, hollow chested, bowlegged, bald, and iron grey at 30, and I was greybearded and white haired at forty. I understand that mother nursed Bill until shortly before I was born, which was in a period when our family fortunes were at their very lowest ebb. Father suffered from malaria and could not work steadily when employment was obtainable, and had nothing to draw upon during the seasonal shutdowns hence, our family poverty. If there is any connection between the facts detailed here and the physical difference between myself and Bill, I am glad that it is I who am the weakling and not he, as I feel that I have offsetting resources which compensate and have got along quite well to date as I am, whereas he could not have accomplished the things he has or survived without the strength and stamina he possesses.

Joseph Fleming left, Bill Fleming right, about 1895

As a pupil at school I was probably average as compared to my contemporaries by the standards of the time. Certain studies I practically ignored altogether, in others I trailed along inconspicuously with my class. In reading, history, geography and drawing I seemed quite above average in ability. This was probably due to a personal interest in these subjects whereas, grammar bored me, and arithmetic applied only when presented in puzzle like forms that aroused mu curiosity and reasoning instincts.

During 1893 and 1894 several short trips to Rondout (Lower Kingston) widened my horizon and sphere of interest. I felt quite traveled and acquired a liking hum and activity of city life. In November 1894 our household was quite upset by the running away of my oldest brother Jim who having had trouble with the son of the job superintendent, punched the guy, and fearing my father’s displeasure, pulled out of town altogether heading for Philadelphia from which he shortly wrote home, considerably easing the family worry. My brother John, then a water boy on the same job, was given Jim’s job and the boss, a real friend of fathers’, suggested that another of the family take the job of water boy. Brother Bill was about 15 then and satisfied with the job he had with another company. I was 13 and small, but was allowed to take the job which I today blame for a flat chest and round shoulders. I only worked a brief period in 1894 when the winter shutdown came. I resumed work the following March, holding it until the place was destroyed by a tremendous cave in on December 19, 1899.

During 1900 I had five jobs of short duration for the same management at other points. These were: working on road clearing, shoveling coal on the kiln head, working in a sand pit, assisting around the fire room and compression plant on the night shift, and later helping the blacksmith down in Black Smoke on the opposite side of where I nearly lost my life in 1899. In 1901the same management sent me to the new job in Lawrenceville where I worked until that plant was closed by the Trust as a local consolidation was called. I was then returned to Black Smoke as a Mucker, remaining there until that job closed permanently sometime in 1902. On October 14, 1902 secured a job at the Beach Plant between Lawrenceville and Binnewater, working there until about December 1907.

I was shifted around a great deal on the Beach job, but for most of the time, had jobs to my liking. I ran a belt conveyor that supplied coal to the engine room, and I also attended a bucket car that supplied the kiln head with required coal. I also looked after the unloading of the coal cars and usually the hoop heading and stave carload lots that arrived. I placed and tapped much of the oil used and cleaned up the sortings thrown out from the cracker room. I tested fire hose, hydrants, refilled and refreshed fire barrels, piled staves, and cleaned bricks. I usually had about six to eight Austrians to direct on much of the work here mentioned, at other times I was alone and did as I pleased as I stood in well with the bosses and defeated various envious attempts to oust me, attempts which earlier caused me considerable hardship.

My best hold on this job was winning the friendship of a new boss whom I knew only by heresay and fully expected to disagree with. To my surprise I found him very square with everybody and while expecting a good day’s work, he was by no means severe on anyone who tried to suit, even when the work was too much for them. These generally slid into lighter jobs. His personal friends, he for the most part put on piece work, virtually forcing them to work and still retain their friendship. He practically built a job for me and during occasional absences gave me his own responsibilities of assistant superintendent. Years later in another town, I boarded with the man then dying of consumption and in poor financial circumstances and I will always regret that shortly after his death, to save my own face, from a humiliating disappointment, I was obliged to hurt the woman we both loved.

December 25, 1941

I spent about five years on the Beach Plant, where for the last two seasons I was particularly satisfied. I will never forget the autumn of 1907 as I observed it there facing the multi-colored mountain with considerable time and peace of mind to meditate upon the grandeur before me. I was at that time already saturated with poetic readings from the masters. I had just memorized the Rubaiyat and already had become fascinated with the beauties of George Sterling’s A Wine of Wizardry which had only recently appeared in the Cosmopolitan Magazine. The job had shut down and never reopened. About midwinter I was laid off after help conditioning the old “Mad House” for use in a local smallpox epidemic. That section of town afforded a fine view which pleased me much despite the cold and inconvenience of the weather. I got done there in early February and then ensued then one of those dreadful periods of idleness which I and my family knew all too well.

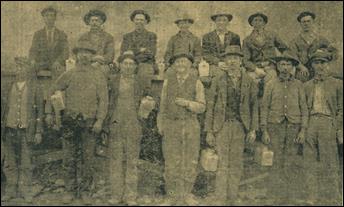

This time however, the coming of spring offered no hope of relief in the way of operations opening on the cement works most of which were permanently closed and some already dismantled. March came along wet, dreary, cold, monotonous, and without hope. I was discouraged. During the first week of April, a gang of localites including myself were through the good offices of a local politician given jobs on a newly begun Macadam Road on the outskirts of the village.

We worked like slaves in our anxiety to make good the first day. Our foreman, a big stern looking businesslike Ohioan watched us narrowly for a while then called a halt for instructions. He told us that we would find him hard but not brutal and unreasonable. Experience told him that our pace was not a ten hour gait and the only result of our trying to keep it up would be playing ourselves out and unable to do anything for perhaps a week, thus losing our jobs in what he already knew it to be a very hard local period. “Go easy, and harder up the rest of this week” he advised, adding that after that expect no “breast milk”.

As promised we found Burt quite exacting yet by no means cruel or unreasonable. I was sorry to see him transferred about two months later and replaced by a Pennsylvania Dutchman who however, proved to be a fine fellow, not very exacting and quite easy going a fellow apparently sliding down from high positions because of drink. All through the summer and early fall of 1908 I worked from the Coxen Bridge to High Falls Village under for the most part, pleasant conditions. The work was moderate, the scenery was beautiful, the outdoors invigorating, the neighborhood girls friendly, and I was young. In October we shifted to Cornell’s Hill where for a month more we engaged under similar agreeable conditions and wrote finis to an episode in our lives. There was black idleness again for about six weeks.

I had applied for work at one point on the Water Works at High Falls without results. Later riding up through Stone Ridge with Brother Jim who was collecting on his insurance debit, I saw a series of snow huts and dilapidated ramshackle shelters used by foreign laborers on that section of the project. (I later wrote an essay on this impression) On the return home we met two Rosendalers. Having room for only one to ride, they refused to separate. A little further down, we overtook a father and son. The father readily accepted Jim’s offer for a lift. This man inquired if I was idle and offered to ask for a job for me. The following Saturday night, he sent word for me to appear on the job the next morning. Despite a dislike for Sunday work, I trudged the four mile stretch next morning and learned that the boss was a friend of mine who would have held the job open a week for me if necessary.

The work was chiefly handling heavy timber, piping cement, machinery and other supplies. Heavy lugging in mud, ice, rain, snow, and intense cold. Many of us were weaklings and could never have withstood the strain under another boss. Bill Smith was a gentleman. In ill health himself, he tried to make everything as easy for everybody as the nature of the work would permit. He was above misusing an enemy. Illustrative of his character is an instance where he came to me as a friend and asked me to oblige him by taking on certain hard duties. “I’ve got no one else free just now but so and so, and if I put him at it, he will say I am picking on him because we don’t like each other”. There was a man!

High Falls had already taken on an aspect of wilderness. Danger lurked in every step, particularly after nightfall due to the influx of a non de script element part gentile, part riff raff and scum embracing many nationalities. Some of these followed capacities essential to the undertaking; others were parasitical and formed the most dangerous elements. Robbery and assault became frequent. Murders averaged about one a week within a three mile zone of our contract. I had not as yet contacted the worst elements, but later taking a job as blacksmith’s helper at shaft 4 I soon made many undesirable acquaintances and still later when obliged to work nights felt the menace of their thieving and murderous instincts. I was later shifted to Shaft No. 5 where my position was more exposed. While there, I conversed with a man who was murdered a few hours later.

Tragedy stalked in other forms. The accident toll was heavy, and the fatalities in proportion. Involved in a strike, I returned to the lumber yard where Brother Tom was then working. The yard was then in the charge of Eddie Wilson, a rollicking Irish broth of a boy from Dublin who beneath a wisecracking exterior, bore a warm heart and a gifted poetic mind. My sojourn there was short due to my former master mechanic, a Spanish Irishman named Murphy, picking me up on the road one morning and after scolding me about the mix up, informed me of an expected vacancy in the machine shop and offering to recommend me to the Dutchman, as he called the shop foreman. A day or two later the machinist foreman came after me. I found him peculiar, but a decidedly good fellow and spent nearly four years in his employ during which time I did various machine and blacksmith work, iron work, repairing and fireman’s duty. It was all over for everybody July 1, 1914.

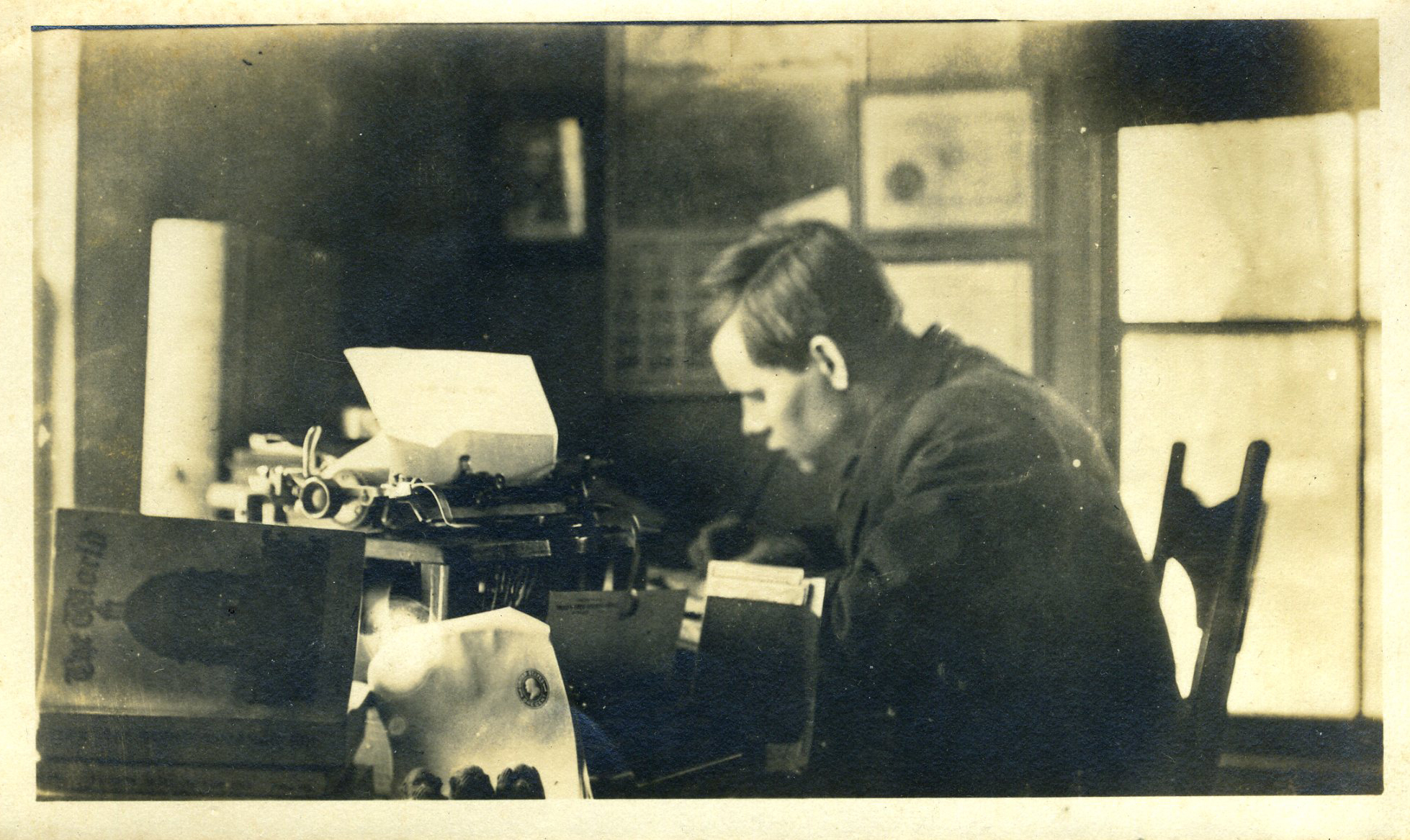

I then got a short time firing a boiler on another vicinity state road, painted a building or two with Brother John, and helped in harvest and silo filling on the Ackerman farm. After this I spent about three years in Walden NY working as a blade dropper in Schrades Shop. Walden was then a pretty town, somewhat larger and livelier than Rosendale, with band concerts, movies and proximity to the then wide open Orange Lake Amusements. I enjoyed its wider outlets, but wishing to locate in a city near home, negotiated for and finally obtained a job in Poukeepsie at the Separater Company, starting there in January 1917. I was in the employ of this company for about nine years operating lathes, planers, and milling machines. Finally in July 1926 I got caught I one of their frequent big layoffs and walked out the gate with the sense of relief one experiences when the inevitable and long expected blow has fallen.

This is a rough sketchy outline of the first forty five years of my life. Between the lines lie many stems of interest which I hope to detail in other writings. Thus closed a period of conditioning and background building which gave me the perspective with which I view the major experience of my life amid an altogether different call of people and environment. Whatever faults may be discerned in my appraisal of my latter day environment may be traceable to the background of a half literate poetry loving studious laborer, inherently committed to the eternal virtues, scornful of hypocrisy and wrong doing however cloaked. One conditioned in a way of life that calls a spade a spade, despite a considerable knowledge of the lingo of the learned, may here and there for emphasis or descriptive values revert to the old forthright simplicities that hit the nail on the head.

In September 1926 I went out to Arlington to see and old friend and townsman Eugene LeFevere who had often suggested that I take a job at Vassar College saying that I would never regret it. Adding that I would like the people there, and they would like me, and as soon as they found out the type of fellow I was, I would get tons of reading and oceans of help with my writings and general educational improvement. Virtually the same opinion was expressed by a foreman at the Seperator with whom I had boarded nine years but the very opposite was the prediction made by a downtown socialist friend who advised me to be cautious if I intended to hold a job among the intellectuals there. “They don’t want your type. You are too honest and intelligent and can see through them and they’ll know it. Watch out for Christians, humanitarians, and intellectuals. They are the cruelest types in the world at heart. Their public professions are usually smoke screens to hide their conniving rascality. You won’t get fired; you’ll get de woiks and take a run out powder of your own accord”.

Mr. Perkins was one of the leading Socialists of the Poughkeepsie Local which claimed various Vassar faculty and students among its membership. He ran for member of assembly from the Poukeepsie district, presided at Socialist meetings, and made many campaign speeches thereabouts during the First World War years. He was one of my best friends, although we disagreed and argued incessantly. Each of us conceded the other to be honest and well-meaning according to our own lights, but yet benighted purblind and ignorant. A thorough going Yankee from an obviously refined and cultured family, he was beyond question a gentleman. A profound reader, a lover of poets, and a man of evident scholarship. He never met my father but claimed him as a brother, a kinship betrayed by my habit of frequently quoting from father’s Burns-like tirades against the causes of human misery. Mr. Perkins often accused me of being tradition bound and mistaking it for character and principle which according to him were merely the result of training in a narrow groove by influences that found it profitable to mold other people’s opinions.

He was an atheist who discovered a Creator claiming that there always had to be something as nothing is inconceivable. He supported the Darwinian Theory which I contended proved the existence of a guiding intelligence at work through the eons and immeasurable cycles of time. I accused him of believing in an effect without a cause and I wanted to know if I looked silly enough to believe that it was the tail that wagged the dog. He had to laugh at that one, and his only rebuttal was that it was in the Irish psychology to want to believe in spiritual matters and the better element of them being intelligent resourceful people; they were capable of building up defense barriers extremely difficult to demolish. “The better element of them” qualification was typical of Mr. Perkins in debate. While he often made sweeping generalizations, he at times qualified and admitted exceptions.

As my father used to claim, “Exceptions prove the rule” I am still in doubt as to the degree of compliment Mr. Perkins conceded to the Irish. Mr. Perkins disavowed bias in all things. I agreed on this point adding somewhat maliciously that his was a pure and simple case of prejudice. He defied me to show where he had ever shown any discrimination in his criticisms of things “rightly under fire” or spare wrong doing, hypocrisy or deceit in any form. Frankly I could not. He denounced the Ku Klux Klan as freely as he did the Catholic Church saying that the Klan merely wanted to substitute on evil for another as Protestantism was no improvement on Romanism “furthermore there is not a fundamentally humane or Christ like principle in the whole Klan ideal. He admired Christ as a truly noble figure and founder of all humane principles and deplored the commercializing of His precepts by the Pharisees. Once in an argument with a fine young fellow he made the assertion that Christ could easily be a beautiful myth built up by the scribes and ancient ecclesiastics as there was no mention of Him whatever by contemporary lay historians. If I remember correctly the young fellow asserted that either Herodotus or Josephus (Flavious Josephus) made certain comments referring to a certain Nazarene whom his followers claimed to be the Christ. I have not to date been enabled to check up on this point, but I certainly admired the young fellow very much and did my bit in helping him out in his argument with a much older, better educated and more widely read man. Mindful of the conflicting prophecies mentioned I started to work at Vassar in 1926. As my experiences there are detailed in another book, I prefer for the most part to keep the balance of this volume to experiences, observations, personalities etc. that I encountered at various points along the road of life jotted down out of chronological order for later sorting and assignment.

My parents were both Irish immigrants. My father James Fleming hailed from County Waterford, and he and brother Edmond left there at the collapse of the short lived rebellion of 1867; first going to France from whence they took passage to America. Certain of my mother’s brothers also came here later under quite similar circumstances; they also having participated in that ill-fated uprising. Mother came to this country in 1871. My parents were married in Rondout, (Kingston) New York in 1873. They were the parents of twelve children, ten of which were boys. Seven boys and one girl reached maturity. I was the fifth child of the family and for reasons earlier mentioned I am the smallest. Sensitive on the point in boyhood and youth, I later accepted the challenge my handicaps imposed and resolved to outdo them all in the values by which the world rates success, although I frankly acknowledge that in terms of genuine intrinsic worth I could never approximate the exemplary life of Brother Bill.

Our Family as a whole was considerably above the local average in intelligence and I fear some of them including myself took this accident of birth with a shrewdness which I now regard as laughable. All aspired beyond their station, a few, (handicaps considered) were moderate small town successes. The First World War carried Tom off just as he was getting a foothold with his printing and publishing plant. I was ever the reader, the dreamer, and the scribbler of well-meant but poorly constructed verse; a fact which in the rough and ready world brought me a considerable amount of respect, but in educated circles seemed to invite affronts from curious probing elements interested in psychological reactions to adverse stimuli.

Call it strength of character, bull-headedness, or whatever you please but I have withstood playing down pooh poohing, ridicule, malicious prosecution, spite work, and sundry other forms of inferiority engendering stimuli, and persisted as far as circumstances would permit in my ways of life, philosophy, opinions point of view and ambitions in spite of hell and the disapproval of kindred associates clerics and working executives. This trait brought me many a heartache as I always wanted to be right and to be understood but despised the arbitrary, the cruel, the arrogant, and the stupid. I fought back openly when I dared to without jeopardizing my bread and butter or my physical and mental well-being and from the inner resources of my heart when I dared not utter a word or manifest an insubordinate thought or emotion. I always admired political outlaws who driven underground, fought for their principles and ideals often without hope. While such types remain in the world, injustice and tyranny shall toss in restless slumber and hope shall spring eternal for the underprivileged, the betrayed, the defenseless, and the wronged. Illustrative of the extreme sincerity of such men is the laughable Russian story about a terrorist under the Czarist regime who was sentenced to be hanged. The rope broke when the trap sprung. “Oh God, help my poor country” moaned the dying man, “they can’t even hang a fellow decently”. This tops the American story of the Indian who said: “My people mad for white man steal our country, hate em like hell. No more that. We fraid now after he spoil everything, he make us take it back”.

High Falls

On March 4th 1909 a blizzard swept through the East and President Taft’s inauguration was held under very unfavorable weather conditions. I was working about a mile beyond High Falls and perhaps five miles from home. A power test at the central plant of the Gillespie Contracting Company required my foreman’s assistance. He had arranged with me the day before to take charge of the lumber yard during his absence. On the morning of March 4th Mother called me about 4:30am and told me I had better stay home as it was storming terribly. Ordinarily I would have done so, but due to the arrangements mentioned, I started out and bucked the snow drifts. It was pitch dark and I lost my bearings for a while, but kept walking. Later recognizing familiar landmarks, I plodded along and finally arrived at work considerably late, only to find no one else at the yard. I looked up my boss at the power house, only to receive a scolding for coming out. He, poor fellow (long dead now) tried unsuccessfully to get me a ride back home.

From about September 1913 to June 1914 I was firing a small boiler at High Falls that powered the pump supplying water for the concreting of the tunnel between shafts 4, 3, and 2. At first the job was a sinecure but later it became very hard indeed. It took me considerable time to figure the trouble out, and even after I did, I was obliged to resort to strategy to have the condition remedied as our boss always took the opposite of everyone else’s position or opinion concerning work details. Our boiler was a fast steaming stationary locomotive type, designed to develop 35 horsepower which it did easily. In about the second month, all hell broke loose. I was shifting one drunken lazy fellow and was in turn relieved by his brother who was a sober hard working guy anxious to get along yet despite our efforts we could not keep up steam while the lazy fellow, although working harder than he liked, got along best of the three of us. This made him cocky and he often stung me for a 24 hour shift. I stood this until his brother laughed at me and boasted that when their mother was trying to get the drunk out to relieve me, he interfered and told her to let Jim go to the devil; never thinking about me handling the swing over of the three shifts all alone. That settled it. I went home and stung them both for a shift apiece. Due to the extreme hardness of the work neither I nor the fellow who caused it got fired. Not wanting to work, this fellow then got his brother and me to agree to ask for more money. He acted as spokesman and had the boss eating out of his hand in five minutes. I got the raise and he went off on a drunk and was replaced by another bum like himself. Sometime later, things eased up so much so that I used to walk down and see if the pump was stopped. Previously I could hear it pounding from where I worked and often umber of strokes per minute. This particular night I counted them again, and to my surprise found that I had the required water pipe pressure with one fourth the number of pump strokes per minute and could easily keep up a full head of steam by giving the fire a little attention about once an hour.

This was heaven compared to stirring up the fire, or coaling it up every five minutes only to succeed in clogging the grates and ruining the fire altogether. Reasoning I thought perhaps less water was being used. Meeting a fellow from Shaft 3 I enquired and was told that the concreting was going along rapidly. I then spoke to Abe Pritchard a colored odd job man at the machine shop if the pump had been fixed lately. “Oh yeh suh, Ah packed it up day before yestiddy” Abe informed me. I then gave him a great pat on the back saying he was the only one around the job who looked after affairs rightly. Things went fine for about a month, and then the pump strokes increased. I spoke to the boss about having it replaced and there I blundered. Just out of contrariness (not meanness) he wouldn’t allow it to be touched, and the devil was to pay for us firemen. I got hold of Abe and coaxed him to do a sneak job on the pump to help us out. “Ahs afraid Joe” he replied “but I’ll make Teddoe (Theodore) make me do it tomorrow”. He kept his word and later confided the process employed which was similar to devices I often used on the boss myself; these being merely taking advantage of his oppositeness and desire to show authority. In substance Abe was routed out to pack the pump at once, merely because he confessed having worried all night because he forgot to look at the pump after being ordered to do so “yestiddy.” That lie earned a quarter tip for Abe who never lifted his hat without reaching out an open palm, porter fashion.

Theodore or Teedie as Abe called him was a good German mechanic and despite some peculiarities, was a fine fellow and a good boss. He learned his trade at Krupp’s famous works in Essen. He came to High Falls with the contractor from New York City to which he later returned. I understand he is now deceased. He always wanted a good job done but rarely complained about the time taken. If a mechanic pleaded inability to do a job, The Dutchman would stand over him and bulldoze the idea into his head. Of wide experience he knew much and augmented what he did with information from catalogues and blue prints the usually accompanied machine shipments. He liked to be asked for information and would give it freely but would accept none from others. Once he held four of us in the blacksmith shop idle a half day merely because on boisterous fellow rushed out to his desk and asked “What the hell are we going to do today Theodore”? Becoming nervous that afternoon I suggested that the other fellow imitate every move I made. My plan was to peek through the doorway until he saw me, then jerk back guilty and run to the anvil and bang it several times with a hammer. He had waited until he had caught four of us and then stormed in and gave us hell. The loud mouthed fellow claimed we were waiting for a job. Five minutes afterward we received about twenty jobs and orders to get busy or get out. Theodore had a sister in New York City with whom he always spent Christmas. Before leaving for the holiday, he came to the shop to distribute cigars among the help wishing each a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. During his absence he appointed no supervisor. We were on our honor. Besides as elsewhere, there were stoolpigeons, although Gephardt paid small attention to them. He was a good fellow.

Big Bill Williams was known for his deadly backwoods Yankee humor that spared none of us. His partner Abe Dunn of mixed Irish and Yankee stock, who fearing oft threatened assignation made Bill the mouthpiece of his devastating slanders; and John Hackstock, (Haystack Hotstuff) a roving German blacksmith whom I assisted and Barney (Barnyard) Heinz a blacksmith about my own age. These two were hard drinking fellows usually jolly and uproarious but at times melancholy and of suicidal contemplation. Knowing this, the crew always had a rope dangling from an overhead beam noosed and slip knotted and inviting. Another blacksmith was Old Joe Morrison, a pompous, fussy and exacting blueprint mechanic. He was third generation Boston Irish. Bill Farrell of High Falls operated a lathe at this shop. Between us we intellectually instigated the fourths of the mischief that went on among the crew. The boss remained neutral and amused. No fights ever occurred. During the summer of 1912 a water war started between us and the powerhouse gang. For a time we got considerably the worst of it as the power house fellows had better equipment than we did. However we finally won out due to our boss connecting several water guns at strategic points and a flanking raid I made which cut off the fireman’s supply just as they were driving our fellows to the wall. When their lines went dead our secret guns opened up and we dammed near drowned the enemy.

My experience on the aqueduct line through High Falls began on January 9 1909 in Gillespie Lumber Yard. About four months afterwards, I went helping Mike Mahoney of Rosendale in the blacksmith shop at Shaft 4. From there we went to Shaft 5, later I returned to Shaft 4 and still later back to the lumber yard for about a month and then to the mechanic shop where between helping the blacksmiths and firing the boiler earlier mentioned; I remained about three years or until all work there was ended on July 1, 1914. I retain many impressions of this great project and the individuals I met there. Camp followers, gamblers, murderers, a polyglot of rascal elements. Drunks, intellectuals, prostitutes, thieves, and degenerates. The best and the worst of the best and worst. Company shacks dotted the vicinity of the eight shafts from Stone Ridge to Buntice Point. Murders were frequent, robbery common, accidents many. The Job was built by methods half way between modern and obsolete. Traction and donkey engines and horses were used for transport. One or two of the new Commer Auto Trucks were occasionally seen exciting interest and curiosity.

The contractor’s car was a five passenger Stevens Duryea. Very few automobiles were in evidence locally then, roads were mostly bad and not adapted for auto traffic. The Gillespie Company had a tramway that carried concrete material two miles. Their power plant contained eight 250 or 300 horsepower Sterling and Heine water tube boilers, ten large compound compressor engines, various large reciprocal and turbine pumps and other modern equipment. Auxiliary plants were located elsewhere along the line. Their stone crushing plant was near Shaft 5. The shaft depths varied from 600 to 800 feet. An underground stream was encountered while driving shaft 4 which taxed the skill and ingenuity of experts to overcome. The Kerbaugh job was largely cut and cover. It adjoined the Gillespie contract and ended at Atwood. Its supply base was at High Falls.

Boss Murphy was said to be of Spanish Irish decent. He was alluded to as Iron Murphy in differentiation to Wooded Patsy Murphy a Yankee looking Ohioan who was boss carpenter; and Red Mike Murphy a husky red headed Roman Nosed Italian shaft superintendent whose Irish grandfather is claimed to have fought in the Pope’s Army against Garibaldi.

Another unusual type was Big Joe Trundjer, a red mustached sandy haired man over six feet tall, broad shouldered and built V shaped like an athlete. Plain and stern looking of face, his voice ranged from a growl to a roar. The man unintentionally frightened or offended many. He knew it and tried to avoid it sometimes like this: “What the hell is the matter with you damn fool? I won’t eat you. I only want to make you understand what I want done”. That was Old Thunder as he was called. A man of obviously wide experience in construction, mining, mechanics, and an experienced diver, he was said to have been a member of the contracting company. Characteristic of his personality and temperament are the following stories:

One day a very old man came poking around the job, peering down the shaft

and watching the general

activity. On seeing him Trunjer roared like a mad bull

“Get the hell out of here dad, before you get hurt”. “See here you young wiper

snapper” retorted the old man “Don’t you talk to me like that. I allus done

what I pleased and went where I pleased long before you were born.” “Now, now,

dad” soothed Thunder, “Come along with me. If you get hurt I will blame myself

for it. I’ll show you around and then send you home in an automobile.

Wouldn’t that be fine?” “All right young fellow” said the octogenarian, “But

don’t get sassy to your betters”. Smiling Thunder led him along pointing out

matters of interest till the old man tired and sat down. Thunder took a seat

alongside and listened to him babble about things in general and in particular

the deep affection between himself and his wife. Foremen occasionally tried to

appropriate Thunder for orders but he just waved them away. Finally the aged

man grew drowsy. Thunder called for a car and personally escorted him to the

home of a relative whom the old man was visiting.

One day a very old man came poking around the job, peering down the shaft

and watching the general

activity. On seeing him Trunjer roared like a mad bull

“Get the hell out of here dad, before you get hurt”. “See here you young wiper

snapper” retorted the old man “Don’t you talk to me like that. I allus done

what I pleased and went where I pleased long before you were born.” “Now, now,

dad” soothed Thunder, “Come along with me. If you get hurt I will blame myself

for it. I’ll show you around and then send you home in an automobile.

Wouldn’t that be fine?” “All right young fellow” said the octogenarian, “But

don’t get sassy to your betters”. Smiling Thunder led him along pointing out

matters of interest till the old man tired and sat down. Thunder took a seat

alongside and listened to him babble about things in general and in particular

the deep affection between himself and his wife. Foremen occasionally tried to

appropriate Thunder for orders but he just waved them away. Finally the aged

man grew drowsy. Thunder called for a car and personally escorted him to the

home of a relative whom the old man was visiting.

On another occasion Trundjer was trying to instruct a gang of Italian laborers concerning a piece of work he was laying out. These fellows were anxious to work but plainly frightened and blundered about often colliding with each other and acting stupid otherwise. Trunjer shouted and swore at them until almost hoarse. He then threw up his hands and ordered everyone to sit down and cool off. After a short recess he asked “Do any of you boys speak English?” One forward and mouthy looking fellow stepped forward and said “Oh yes Mr. Boss, me speakin goot English.” Well now that’s fine.” replied Trundjer “These poor fellows don’t understand and they are nervous and afraid of me. Here! I’ll show you and you explain things to them.” After detailing matters thoroughly Trundjer let the young fellow go ahead. I saw this laughable incident and from familiarity with Italians and the knowledge of a few words of their language surmised the gist of the young fellow’s address to his gang. Preponderantly it seemed to consist of emphasis on the statement that he was now a boss. The rest of it or the many accompanying gestures I did not understand, but saw the resultant confusion of the poor fellows’ efforts to proceed with the work. Trundjer watched them for a minute, and then called the young fellow over to him saying “Tony, did I understand you to say you speak good English?” “Oh yes Mr. Boss” again affirmed Tony, “Me speak good English.” Trundjer grabbed him and threw him into a ditch then walked away in disgust towards the office where apparently he phoned one of the Italian Superintendents for an English speaking countryman as one appeared on the job an hour or two later.

Trundjer was noted for his great ability as a construction superintendent. These abilities were readily conceded by all who worked for him, even men who were local contracting carpenters for years. Many hated him but all agreed that he knew his business. I got into his good graces by checking an engineering diagram concerning a hole designated as 3/4 inches was an error, as I thought it should be 13/16 inches to clear a 3/4inch bolt. I was correct, and he patted me on the back for catching him. The worst mistake one could make in dealing with him was to say you understood a plan and then make an error. If you admitted not grasping an idea he would clarify and checkup as the job proceeded. Otherwise he let you go ahead on it alone. He never came in anger with a job and tried to put you at ease while explaining it, but would raise hell about incorrect work.

I once heard an argument between him and a hot blooded young Southern super who talked tough. Trundjer retorted “See here Fred, I’m a member of the company and if you get hurt here they are liable. You claim you’d hit me if I wasn’t so much older than you. That’s fine. But I want to have this out with you somewhere off the job. Let’s go off\ the company property. Bring your gun along and I will take it away from you and give you all the satisfaction you want even if I am ten years older than you are.” There was no fight.

Daddy Devil

Daddy Devil was a hard drinking foreman who virtually lived on the job. Once in an emergency he is said to have stayed on the job for over a month eating and sleeping in the “Dry House”. He looked and acted like a pushover. Soft spoken, with a southern accent he seemed slow to anger. He was methodical and unhurried in directing the work in which he was obviously an expert. I once saw him climb aloft the head frame to make some adjustment there. It was a bitter cold morning yet the sweat poured from his face although his clothing, soaked from the water of the shaft was frozen stiff. An envious associate of mine commented thus: “Oh byes oh byes, if I had half the rum he has inside him I’d be drunk for a month and I can stand plenty of it.”

On another occasion a colored fellow whom a sub foreman dismissed, came back to the shaft, pistol in hand, looking for trouble. “Wyah ya going wid dat gun colered boy?” enquired Daddy Devil. “Don you mine now Daddy. You just keep ya nose clean. Ah done looking fuh dat dere Old Shotgun what fired me an I done gonna get him plenty.” “Ah son, son,” soothed Daddy Devil, doan you know it ain’t a robust thing for the constitution of a colored boy to try any monkey shines with that ol Johnny Reb what was one of the best men Massa Lee evah had in his hull army, and what is so tough yet dat de debbil wrote God Almighty warnin him he wooden low Shot Gun on his property? Dats why the ole bastard can’t die, deys no place foh him to go.” Y’all just leave him to me Daddy” answered the other. “ Ah’ll send him somewhah. Ahs goin’ to pop him off de minute he pokes his head to de top of da shaft. Wone de fellows down below be surprised when de see Ole Shotgun tumble down rite in de middle and flatten out like a piece of paper. He wone hafta go anywhere ‘cause dey ain’t gonna be nothin’ of hem left.” With a lightning like move Daddy Devil grabbed the gun then yelled “Now niggah, keep moving. Ah’ll let ya git as fah as the road an then ahs gonna burn yuh”. The youth fled, hitting only the high spots. Daddy Devil fired two shots, both of which entered the fellow’s right arm.

Shortly afterwards Old Shotgun arrived from down below. As he limped towards the Dry House, Daddy Devil shouted “See heah you old devil, yuh owe me a quart of rum, Ah just saved yuh life. Wadda you mean anyway, makin trouble fuh me , pickin on one of my nicest colored boys? Dat Mississippi brat was out a gunnin’ fuh ya, but I talked him out of it kinda. Yuh better watch out tho, he mad at you yet.” Old Shotgun’s retort however modified in translation would still be unprintable. Shotgun was an unreconstructed rebel whose right hip had been badly shattered at Gettysburg. A good old fellow though, he informed me that he was at the first battle of Bull Run and the surrender at Appomattox, and he also received two other wounds, the marks of which he showed me. One was a bullet wound and the other a saber cut.

Numerous Southerners both white and colored worked on the aqueduct line. Some of the colored men held responsible positions in which they were capable and efficient. Among the whites I found a variety of temperaments. The younger elements, with few exceptions, were by and large agreeable. The more settled evidenced many of the characteristics attributed to the hospitable South. Among these were quite a few Spanish American War veterans. My particular favorite was a tall military looking , courteous gentleman, who as a small boy witnessed many of the incidents of the Civil War and reconstruction period. He discussed such matters with calmness and objectivity. He was a man of evident education and culture. He seemed reminiscent of the idealized type of Southern army officer, and to my surprise readily conceded the justice of emancipation, yet maintained that Northern economic factors had as much to do with the development of the abolition movement as did humane and ethical considerations.

My association with varied racial elements was considerable. On one occasion when sleeping in the dry house between the “Swing Over” shift change I awoke at dawn. Thirty other fellows lay snoring on the bare floor around the huge stove. I was the only white person among them. I often slept thus on the “Swing Over” or “Short Jump” between the “Owl” and “Day” shifts (the intermediate shift was called the Dead Man’s Shift). Sometimes I captured the prize bed which was the blood canvas emergency stretcher, which was preferable to the hard floor. The shift changes operated two ways. Swinging backwards I did not understand but believe it involved a twenty four hour shift for one man every three weeks while his lead and relief took their time off and vice versa. We always changed strait, that is the owl shift or 4 to 12 returned to work the next morning at 8 o’clock. This gave eight hours off. The dead man’s shift ceased at 8 am and returned at 4 pm, while the day shift finished at 4 pm the previous day and had thirty two hours off before swinging to the dead man’s shift. As I lived in Rosendale and walked to and from work, when I was faced with the short jump, I slept as related in the Dry House.

Traveling at night was indeed hazardous in that locally during that period. Many men were held up and some shot from ambush. We bunched up whenever possible but I traveled alone much of the time. Nearly everybody was armed at that time. I carried an American Bulldog five shooter and always removed or inserted the loaded cylinder at Coxen, according to the direction I was going as often the dogs of Lawrenceville or some drunken acquaintance were often encountered in the dark and I wasn’t afraid in my own neighborhood. Only on two occasions however, was I molested in the High Falls vicinity. On one of these the gun saved me from trouble, on the other not having it with me saved me from serious complications.

The first incident happened in 1910 on the tow path just below the feeder dam. I and all other Rosendaleans always kept to the extreme right when meeting anyone in the dark and always greeted with a friendly hello. In that way we recognized each other. This night was clear and moonlit. Three tough looking fellows approached me obviously intending to close in. I turned and ran back until I got my gun out whirled and fired saying “That was way over your head. I’ve got five more that says I am going home and you fellows are going to stand way over to the right and let me pass without any monkey shine. They moved over and watching them narrowly I passed, but oh the filthy names they called me when I got down the line a ways. The other incident occurred in 1915. At that time I rode a bicycle. Just before reaching the main road at the Top of the Falls I dismounted at the foot of a small hill on my way home. A wagonload of fellows came along headed for Accord and their dog attacked me. Drunk, they yelled encouragement to him. I blocked him with my wheel and got to the top of the grade. I yelled “Call the dog off and I’ll lick the bunch of you!” The trick worked. They called him off and three of them got out. I threw my leg over the bicycle and yelled “I’ll see you tomorrow night right here at the same time. Bring the dog along too.” With that I was off licked split. The next night I was all ready for them but nobody came and I am glad they did not as I was so angered by the incident that I would have surely plugged the dog, and maybe anybody that interfered.

My brother Tom sidestepped a holdup or beating by his quick wit. Walking home in the dusk, he was accosted by three hobos who asked him for a quarter. “I have no money with me.” he replied. “You’re a damned liar.” shouted one of them. “We know it’s payday. Come across or take a beating.” “Alright” said Tom. “Wait until the fellows just around the turn get here and I’ll borrow some change from one of them.” Off guard for a second or two they looked up the tow path. Tom shouldered the fellow nearest him and hellishly hooted it for Lawrenceville, which according to his own calculations he made in nothing flat. Tom was younger than I and a much bigger man and would have put up a nasty fight, but thought the odds too great to take a chance. As he put it “I’d rather have them say, there he goes than there he lies.” Poor fellow, he later died in France during the First World War.

Very near the scene of his holdup I got one of my worst scares. I was walking down the hill from Shirley’s Loch in Coles Basin one evening at just about dusk. The tow path seemed clear as far ahead as I could see. Suddenly, out of the very ground it seemed, a man rose up before me and as he came up I went down. “Hello” he said “What’s the matter with you?” I could hardly answer him. It was a Rosendale fellow who was out setting muskrat traps. He had been crouching over one halfway down in the abandoned canal when I came along. I was ashamed to own up being scared and told him that I hadn’t been feeling well all day. He offered to go home with me but I told him I felt strong enough to make it alone.

High Falls was a polyglot settlement in those days. On several occasions I found myself in gangs where English was only rarely spoken. On one of those occasions I met the handsomest looking man I had ever seen. I was among about fifty Italians during a noon hour. I understood but very little of their conversation and noticed a fine looking fellow who neither spoke nor was spoken to. Assuming him to be an American, I remarked that I wished I could understand Italian as it sounded fine. Musically he replied in broken English, “I can pick out a lot of what they are saying. I am Spanish and find Italian or French easy to guess at.” Previously one of the gang, a little old Italian sailor, had told me he could talk Spanish and Portuguese. I called him, and for the first time listened to a conversation in Spanish. Later I met quite a few of that nationality in and around the Shaft 3 section at Stone Ridge.

The Italians were represented in practically every line of work, contributing many mechanics foreman Superintendents and laborers. On one occasions a gang of these laborers went on strike and marched along the line stopping work elsewhere. When they reached our section a polite intelligent member of their group started to address his men. “Fellows, please stopa work. We are out for more wages. We work very hard and erna more but da boss he call us a goddam wops and tell us to gota hell. So we stopa work, and ask you to please stopa too.” “Here here” get the hell out of here yell our boss rushing up to the speaker who retorted: “Hld horses plez. Now you get excitement. I aska you nice. I say plez stoppa work, now by jeza kries I tella you stopa and stopa right away. Waluse! The cry of Waluse was addressed to his followers who started to move in holding pick handles, mattocks, shovels, iron bars, hammers etc. Our gang scattered as I understand did many others whom the polite young fellow approached. The strike was settled before the day was over. Whatever Walu means in Italian, at High Falls it was applied to Italians in the same way as Wop or Guinea. Strangely the Italians rarely resented these terms and good humoredly use them in addressing each other.

Poles and Hungarians were quite numerous, and often camped together in company shacks erected for the purpose accommodating the Negro and European elements. In 1910I worked very near a Hungarian settlement and became acquainted with one of the girls there. We often chatted on summer evenings, and her parents seemed to trust and like me. The girl herself admitted wanting to marry someone not Hungarian. The family kept boarders who slept in a partitioned section of the shack. One morning I noticed Catherine slip a close line noose around one of her pretty ankles, open the door of the men’s quarters and call them for breakfast. I jollied her about it later and she replied “Oh you don’t know Hunkies, or you wouldn’t say that.” Sometime afterward I heard a racket one morning. Looking out, I saw Catherin’s leg sticking out of the door and heard her screaming at the top of her voice. I ran over but the whole family was there ahead of me armed with an assortment of emergency weapons. They half killed the fellow before he got out of their clutches. I never saw or heard from him again but I will never forget his barefooted half-clad bleeding figure limping through the snows of a bitter winter morning.

One of the best liked men among those that knew him was a terribly disfigured man who I understood to be the sole survivor of a great mine tragedy. He had neither eyelashes nor eyebrows, his hair was completely gone and his face was a total scar. Women with abundant mother instinct for attractive looking males shuddered in loathing at the sight of him, but among the males he was highly popular. A capable foreman, pity for his misfortune, and an appreciation of his many fine attributes readily won for him the respect and affection of all the men.

Shorty was from Brooklyn and made up for the deficiency of his size with wind of which he had a super fluidity. A good singer, we classified him as an Adenoid Soprano whereas Barnyard a fellow worker was alleged to be a Beer Baritone. Shorty was also an excellent whistler. His chief difficulty however, seemed to lie in learning English. We all feigned to understand him except Clarence, who claimed he studied the Brooklyn lingo while in college preparing for a sociological degree. Clarence alleged also to have slummed in Brooklyn variously during his collegiate years to obtain information essential to his main thesis. He always defended Shorty saying “The poor fellow can’t help who he is.” Likewise whenever one of us would want to know what the hell Shorty was trying to say, Clarence would chime in saying “Hold your horses, if you were in Brooklyn you would have as much trouble making yourself understood as he has here. What he is trying to get at is…”. “Oh, that’s it.” The other fellow would say. “Excuse me Shorty. You sounded nasty and I thought maybe you were looking for trouble. Damn these foreigners anyway.” Far from being a martyr, Shorty more than held his own. As often as otherwise, our professing inability to understand him was a defense mechanism. On such occasions Clarence would often shake his head and say “Repeat it Shorty, that’s new to me.” However if it happened to be a bull’s-eye that didn’t apply to Clarence personally, he would translate it freely and often, giving it quarter force and siding in with Shorty.

While firing the Casey Jones boiler as we called it I met many unusual and interesting individuals. Among them were a murderer and his victim, Black Boy and Shorty. The latter had been in my fireroom an hour or two before Black Boy shot him at a shindig over on Pistol Hill. According to a story related to me by a simple harmless old colored man who played the accordion at the dance, Shorty was framed and an attempt was made to whitewash Black Boy on grounds of self-defense. As told to me, an Italian lent Black Boy the gun to do Shorty in. After the shooting, this Italian is said to have gotten everybody together in insisted that they all stick to the story that Shorty pulled the gun on Black Boy, and was shot when the latter wrestled to disarm him. My informant Old Sam begged me not to tell who told me about it as he feared being killed if found out. The frame-up failed however, due to Black Boy’s previous record elsewhere, and the facts came out resulting in conviction.

Old Sam was a typical southern darky. A toil worn harmless old drudge. Not active enough for contract work, he did odd jobs where obtainable. He roomed with a colored washerwoman who supported four little grandchildren who sang and danced and sometimes fought for pennies. They begged bread of passing workmen. The oldest, a very dark girl, divided all food so obtained equally among them with a motherliness touching and splendid. She likewise interfered when certain brutal elements insisted upon her brothers fighting as a condition for receiving a penny. Her sister was the very opposite being half white, rollicking, and indifferent. I had them as guests very frequently, and shared my dinner pail contents with them often. On Christmas Night 1912, our lunch party consisted of myself, Old Sam, the four pickaninnies, two cats, a starving foxhound, and a one eighth tamed catamount. The crumbs were saved for a starving crow that came around daily, and a piece of Christmas cake was thoughtfully taken home by the little black mother of the flock for Granmammy.

These children often spoke about Sister Annie, an older girl I gathered, who worked way off somewhere and occasionally sent money home. Imagine my surprise one evening when they came along and a splendid looking girl as white as any Italian or Spaniard I ever saw. This was Sister Annie, a quiet, reserved and well-spoken girl obviously aware of certain cultures and the dangers of personal beauty to one of her caste. She looked to be about twenty years old. Her taste in dress was refined and artistic and spoke with a lovely southern accent. She was at first reserved and ill at ease, but gradually thawed as the children prompted the fire on, and I paid no more attention to her than common courtesy required. “The chillum all crazy ‘bout you,” she remarked “an Granmammy say to thank you. And I wants to thank you too. We got it hard. Mothah was bad, that’s why me an Lilly is white. She daid now, and maybe de Lord understand huh bettah dan de people. Ah know ah do.” I further learned that there mother was a beautiful mulatto who “ran with white men.” Although married to a pure blooded Negro. Annie’s chief criticism of her mother seemed to be that she was too cheap. “She could have married a white man if she wanted. Now see the mix-up we got. Half of my brothers and sisters have to stay poor just because they’s colored and that ain’t fair. Ahm gonna marry a white man what’s well off. You just wait and see. An I hope Granmammy lives to see it poor soul. She’s one slave what Masse Lincoln never freed.” I found that the girl, despite a mere fundamental education, was intelligent and well-read to a surprising degree and I have no doubt that she eventually married into better circumstances, possibly a white man as was her hope. Throughout our chat she maintained a degree of poise and reserve which dissembled in a very warm hearted handshake at parting.

The night watchman on this job was a quiet hardworking Polish fellow whom I found amusing, interesting and something of an object of pity. He worked twelve hours a night seven days a week. He spoke but very little English at first, but under my tutelage he soon picked up a lot although he found it difficult to understand others. “You speak easy Joe.” he frequently remarked to me, “Oddeh mens speak hard for me.” This fact was due to my considerable experience with foreign elements to whom I spoke in a greenhorn patois such as they used themselves. This fellow’s name was also Joe. He had a family and about five acres of land in the Old Country and was saving up to go back there. He confided that he had nearly three thousand dollars saved up and intended to go home in 1914 as he was an Austrian Army reservist.

The English lesson I gave him were humorous simple and effective. “Wot you call him Joe?” he would ask. “Oh, this coal Joe.” I would reply. “Coal see?” “Little fella piece of coal. Big fellow lump of coal. Fire eat coal. No got coal anymore. Got ashes. Ashes nice for finger, just like dirt. Big ashes no nice. Is heavy, hard like stone. You see? Dis fire, dis ashes, dis coal, dis cinder, dis stone. Stone just same like rock, no difference see?” and so on sometimes to a ridiculous degree perhaps, but the results warranted the trouble although Joe persisted in using words he liked to describe similar things. When corrected he would shrug and say “same ting, an easy for me.”

One night Joe overheard a commotion among some nearby chickens. Going over he saw a “kitty” carrying off a young chick. Clouting it over the head, he brought it back to my room. I looked at it and ran out shouting to him to take it away which he did. His clothes were saturated from the skunk yet he seemed unaware of it and couldn’t understand what I was laughing at. I grabbed my nose and asked “What smells Joe?” “Oh got dam Joe, I no can hear him stink noddings. Me ketch him young jackass last week and me no can stink like hell some more.” Truly translated, Joe meant that he could not smell anything because he had caught a cold (colt) the previous week and his nose was blocked. With him, every horse and mule was a jackass. He liked the word and thought it sufficiently descriptive. Joe was not brutal and was kind to animals. He was sorry he killed “poor kitty” and confessed shock and anger because of a certain act of impropriety. Between us we had tamed a half wild stray cat which I called Thunderbolt due to its lightning like movements when alarmed. Thunderbolt gradually became so tame that he followed Joe on his rounds and rode back piggyback on the watchman.

Joe would often come into the fireroom between rounds and drop exhausted into a seat and fall fast asleep relying on me to wake him in ten minutes. Out of sympathy for the poor fellow I thought it would be to his benefit if his time clock should become in need of repair and said so. The idea alarmed Joe. “He die I got no job.” Was his comment. Nevertheless I played with the idea and occasionally as Joe slept I would grab a pinch of coal ashes from the ash pit, drop it on the keyhole of the time clock and blow on it. Gradually, a sufficient amount of grit got into the works and one night Joe came in crying. “Clockie die, clockie die. What for me do now? Me got no job.” I told him they’d get it fixed in a few days and told him he would have it easy and make only a few rounds a night until the clock was repaired. Inconsolable, he wept with anxiety and made his rounds as faithfully as usual for a week without the “tattle tale” and was overjoyed when it was returned to him.

Joe left for his home in Poland early in March 1914. I recall the night he was due to sail as being very stormy with high winds. I chuckled with glee at the thought of Joe’s state of terror on the high seas. I had no idea of the hardship in store for him. Hardships from which I have often wondered if the poor fellow survived. Here was a man going home to his far away family after years of drudgery in a distant land where he had saved a small amount of money that according to the standards of his country at that time represented an independent fortune. A few months later the world was aflame with war and his country suffered cruelly. As a reservist he was probably called back into the army and his chances for survival seemed doubtful.