My Father

Forward

Aside

from the feeling that I have here discharged a personal obligation to the memory

of my parents I

believe

that it is to a considerable degree a representative account typifying the

struggles vicissitudes sacrifices and problems of millions of immigrants to

America and their individual contributions toward its development and

enrichment. The bias of blood

making detachment and objectivity impossible, I offr as authentic many facts

definitely established. Others in

the nature of hearsay, folklore, humor, and tradition while dubious, did not

lack support in my boyhood days.

Openly sympathetic, I feel that were I to approach them otherwise I would not be

capable of understanding or interpreting them.

My father was a

man far above the average intelligence found in the working class in which he

ranked lifelong. The earlier

generations of his family seemed to have been at least moderately circumstanced

as I understand that one of his grandfathers owned two good sized farms, and the

other engaged in the retail business.

One of his uncles was a Catholic priest.

My grandfather and a brother were carpenters.

I recall father relating an interesting story in this latter connection.

Grandfather

Fleming kept several special boards seasoning for years on the rafters of his

workshop. The day before his death

he instructed his brother to take his measurements for a coffin to be made out

of the boards mentioned. Father,

although very young recalled watching his uncle making the coffin while

grandfather was still alive. This

probably occurred in 1850 or 1851, as Aunt Ellen who was born in 1850 was an

infant at the time and father was only a child of five or six years of age.

Grandfather

Fleming had participated in the rebellion of 1848 and took part in the assault

of the local police barracks which he had earlier helped to construct.

He also fought with Thomas Meagher in Belgium in 1829.

James Fleming was the father of five children, two girls and three boys.

Mary died while still a child, and Ellen died in her twenties.

Uncle Edmond came to America and was killed while working on the railroad

in 1870 in his 22nd year.

All three of the

boys were in the rebellion of 1867 and father and Uncle Ed took part in the raid

on Canada in 1870. Uncle John never

came to America but lived for many years in England.

He seemed very well to do as

did his cousins john and Mary Fleming as father and brother John inherited

considerable money from them.

Grandmother

Fleming widowed with five small children was supported by her brother the

Reverend Edmond Phelan, a Catholic priest who practically reared the children

and gave special education and training to his namesake Edmond Fleming whom but

for his untimely end would have probably followed in his uncle’s footsteps.

Grandmother Fleming died around 1890 and seemed to have been at least

eighty years old. Father was born

in 1846 and died in 1910. Uncle

John was born in 1844 and died in 1912.

Father’s home

town was Carrick on Suir in County Waterford Ireland where they seemed to have

been rooted for centuries, having arrived in Ireland in 1066 with the Norman

invasion and are said to be descendants of Flemish archers whose prowess with

the crossbow contributed to the success of that invasion.

Of note here is the fact that my grandfather served with his personal

friend General Thomas Meagher of Waterford in the Belgian war for independence

in 1829.

Father

immigrated to the United States in 1867

via France and worked at railroad building across the country until he married

my mother in Rondout, New York (Kingston) in 1873 after which he engaged in

bricklaying until locating in Rosendale township in 1876..

For the remainder of his life he worked in the cement mines except for a

few years as a cemetery sexton..

After residing in various Rosendale districts , he finally located on James

Street in 1883 and our family now number among the few very old residents there..

Father and mother had twelve children,

two girls and ten boys and of these eight lived well beyond voting age..

As of this writing (1949) five are still living..

An extraordinary

man and a very unusual type for a common laborer, father possessed breeding,

refinement, and surprising intelligence.

A student, bookworm, orator, and a deadly wit; he had no local equal as a

debater. Even the combined efforts

of intelligent sons to gang up and get him confused only resulted in amusement

for him and frustration for his smart-alecky scions.

Of established honesty, he was empathetic, almost fanatic in his

well-grounded and wholly defensible convictions.

He lacked prejudice, save for the things he held in common contempt; for

such his contempt seemed tinctured more with pity than scorn.

Religiously inclined and well versed in

ecclesiastical lore and concepts, he often openly denounced inconsistencies and

unchristian attitudes of many individuals, even those of his own faith whom he

thought disregarded their commitments.

As a father he

was extremely kind and never punished any of his children and even resented

mother’s efforts to maintain family discipline.

Politically he was a Republican until later becoming interested in Henry

George, he finally embraced such progressive doctrines as did not run counter to

his religious beliefs. Always a

staunch laborite, he was a last ditch fighter in The Knights of Labor local

problems often at great personal sacrifice and financial hardship despite his

intelligent awareness that his loyalties were misled and in some instances

betrayed.

Discussions concerning his

people always saddened father and he seemed to reproach himself for not

remaining with his mother and sister during their lifetimes.

That his family was highly respected was indicated by the attitude of

various County Waterford people who frequently called upon him in this country.

All of these people spoke highly of father’s family, and from them I

learned many favorable family facts concerning which father never bragged.

Apparently our family line was a slow dying “old house” and father

admitted to me that were it otherwise he would have never married.

His wise selection of my mother introduced a strain that matched his own

for character and intelligence.

Father differed

from most of his contemporaries many of whom were gregarious, rough, bearded,

brawling, hard drinking and uneducated.

While though mixing in organizations concerned with political, labor, and

nationalistic matters, he was temperate, clean shaven, well spoken, and widely

read. Always a profound student, he

was familiar with the best literature of the ages.

He loved poetry, read the bible freely, was well versed in Irish,

English, and American history, and had a fair knowledge of general history.

His deep interest in ecclesiastical writings evidenced a strong religious

tendency. Catholic, Irish, and an

active rebel, he liked England and its people, among whom he spent several years

in his younger days. Catholics and

Protestants alike conceded his intellectual honesty and personal integrity.

While his opinions often displeased many, strange to say, he made few

lasting enemies, and in these he took especial pride.

Father never

inflicted any of his private “isms” on any bored or disinterested individuals.

His policy seemed to let the other fellow lead off and follow him up

step by step either to agreement or otherwise.

One of his best friends was an Episcopal minister, a native of the Isle

of Wight and a personal friend of Alfred Tennyson whom he somewhat resembled.

They usually discussed English and Irish history and literature.

Religion was rarely mentioned.

Both of them could quote Bobby Burns in good Scottish dialect.

Other topics ranged from Socrates to

John Brown of Osawatomie.

Father, from

personal choice, liked to keep record of time in the same fashion as did the

illiterate “owld stock” for ages.

He quoted dates only when omitting them would cause confusion.

Examples follow:

· Vinegar Hill Rebellion 1798

· Impeachment of Hastings 1788-1795

· The time of “Bony” 1815

· Emancipation Year 1829 (Roman Catholic Relief Act)

· Night of the Big Wind 1839

· The

Famine Year 1846

· The Rising of ‘48

· The Crimean War 1854- 1855

· The

Indian Mutiny of 1857

Other

dates were indicated in conversation

with those that understood by such allusions as

The Fenian Rising (1867),

Disestablishment of the Church 1869, and

the Phoenix Park Murders (1882).

American dates were implied by reference as well such as

The Tilden Trouble (1878), Grants Term

(1869 – 1877), The Potato Bug Year and

The Blizzard (1888). Local

periods were mentioned as

The High Water Spring (1878) and

The Binnewater Strike (1888).

One reference has an interesting family

connotation was the year Mike Foley Jumped the “Ha Ha” (1852).

Mike Foley was a

neighbor’s child who adored my great grandmother who until 1841 kept house for

her son, my grandfather. He married

that year to the great dissatisfaction of the Foley child, as the new bride

seemed to be displacing him as the center of attraction.

He asked great grandmother to put the new woman out.

She told him that he should speak to the son about it.

This Mike did at once. My

grandfather seriously confided to the boy that he did not want the woman there

himself but could do nothing about it as she was a stranger to him and he was

afraid of her. He then asked

Michael if he would please order the woman to go away.

Glad of the chance, Mike issued the mandate.

Grandmother Fleming meekly consented to leave as soon as she could get

someplace to live. She fed and cajoled

Mikey and asked why he didn’t like her.

There seemed nothing in particular.

He was finally won over and ever afterward was her constant friend.

The “Ha Ha” was

a hidden fox hunting hazard, a horse jump that killed the Marquis of Waterford (Henry

Beresford, 3rd Marquis of Waterford)

in 1859.

My father saw young Mike Foley clear it in a running leap in 1852.

This same athlete often tottered into our Rosendale home to talk about

old times in Ireland with my father.

The sight of this palsied old man always touched my father deeply, and

caused him to recall the famous young jumper of bygone days.

Incidentally, Mike Foley and his cousin Jim who also lived in Rosendale,

both carried a pike in the rebellion of 1848 in the same local unit in which my

grandfather served.

In the 1880’s

The Knights of Labor and the Hibernians were strong.

Father belonged to both.

They died out due to the decrease of Irish immigration, combined with the lack

of interest on the part of American born generations.

Colorful and impressive, the Hibernians were quite typical of the many

and diverse fraternities which were then in vogue.

The Knights of Labor being cosmopolitan was then the largest local

organization. It’s back was broken

however in The Binnewater Strike of 1888, after which local labor units were

weak, covert, and largely underground.

Having a young

family to support, father often helped in the ice harvesting along the Hudson

River. There were no felt boots

then and leather boots were generally worn by the workers.

In addition to the few hard earned, sorely needed dollars, father often

contracted frozen feet and a cough that lasted deep into the summer.

This in addition to seasonal attacks of malaria, hard work, worry, and

family responsibilities, practically wrecked him in his forties. All these

bringing on a light paralytic stroke after which he aged rapidly,

yet struggled along in his laborious

work until his death in 1910. Commenting

on latter-day advancement, father enshrined the inventor of felt boots among the

greatest of human benefactors and welcomed the advance of labor saving

machinery, hopefully expecting them to eventually become government property

used to ease the burdens, shorten the workdays, provide work for the vigorous,

abolish child labor, and facilitate pensions for the ill and aged.

A man of great

feeling, his intelligence intensified his sufferings and recognition of his

hopelessness of his lot caused him keenest mental anguish.

Without any evidence of self-pity he

regarded his problems as part of the lot of class in his time and generation

which bad as it was witnessed advancement and human progress toward the Utopia

of his dreams. A lifelong slave,

his only personal hopes were in the hereafter and he often said “Whatever is

ahead, let it come. I don’t want to

go back”. His sympathy for

others, love of children and animals, and his pity for misfortune was boundless

and extended to every living creature.

While engaged as

a cemetery sexton, he was painfully impressed with the neglect of children to

care for the graves of their honest hard-working parents.

Often out of sheer indignation he without recompense, cleared the weed

grown plots of parents who had left substantial sums to their children.

Beautiful tributes to his personality were evidenced in his close

attention to the Potters Field and unconsecrated sections of the cemetery, his

care of young wind-sown seedling trees, and his avoidance where mother birds

were either hatching or rearing their young.

At home he often

kept as much livestock as would not interfere with his gardening,

He kept a milk goat, ducks, pigs, two dogs (usually terriers, collies,

and bulldogs), a flock of excellent tumbling pigeons, and many game fowl.

The only trace of cruelty in his nature was the fact of him using these

game cocks for fighting purposes.

He rather lamely and shamefaced tried to justify this practice by saying it was

their nature to fight. This was a

point upon which he disliked being twitted.

He was a sportsman, having caught the fever when very young

and although loving the beautiful

creatures intensely, could not resist demonstrating their fight to the death

qualities. As before stated, the

men of his class were, in the rank and file uneducated, rough, and often devoid

of refinements. The influences of

associations and environments certainly played a part in father’s life which

while altogether changing his true nature, at least accounted for some of his

inconsistencies.

Fiery himself,

he admired fire in a dog, gamecock, horse, or man.

A boyhood follower of horseracing and fox hunting, the yearn for such

removed pastimes never left him.

His living political hero was O’Donovan Rossa “The Irish Dynamite”.

He revered such Irish patriots as The Emmets (Robert

and Thomas Addis), Wolfe Tone, The Shears Brothers, Lord Edward Fitzgerald

and many others. Father always

pointing out that whenever Catholicism was crushed and submerged, Protestant

Irish demonstrated a type of patriotism which Catholic Irishman held in the

highest esteem. He often quoted the

protestant poet Thomas Davis in support of the assertion that such “outsiders”

as the Geraldines (FitzGerald),

Normans, Flemings, and even the English, often became more Irish than the Irish

themselves.

Speaking of

poets, father admired Tennyson, Longfellow, all the Irish poets, and Bobbie

Burns, the latter being his favorite.

He sometimes whimsically tried verse himself.

Some of these effusions I may include later.

It was only during the last years of his life that I was of sufficient

mental maturity to regard much of his extremist philosophies as other than the

rantings of a crank. As I progress

with age myself, I see ah how regretfully that I did not understand him.

Father was a man far ahead of his time in many social ideas, some

permanent fixtures while others in the offing, yet he never could have been a

success. The man was too honest,

too sincere, too radical, and fanatical to ever compromise with intrigue,

rascality and hypocritical diplomacies associated with many types of success.

Thank God for the normalcy, intelligence, and common sense of my mother’s

strain which toned and tempered our family heritage. Father had the impetuosity

which scorns caution, blinds one to the consequences and makes martyrs.

Strategically inclined enemies could cause him to play into their hands

and so destroy himself.

As I developed

in knowledge and experience, I saw the truths in father’s ravings but also

realized that we lived in a small narrow neighborhood, where few understood

or sympathized with such ideas.

Critical generalities often hit too close.

Neighborhood loyalties were offended, cliques were enraged, employers

embittered, the intolerant hateful, and friends alienated.

Such a situation was untenable and suicidal and my mother was very much

upset. Pointing to these factors I

persuaded my father to pipe down for the sake of our family and write a book.

He consented after a long citation of precepts supporting his point of

view and attitude. These ranged

from The Sermons on the Mount,

Thomas à Kempis,

Victor Hugo, Voltaire, Harriet

Beecher, and Dicken’s Wilkes Micawber.

From unidentified sources came phrases such as “Letting the truth be told

though the heavens should fall, and the virtue of having the courage of having

ones convictions...”.

Father did

however start a book, the range of which was confined to the village limits.

This he died without completing, and

the manuscript I have yet to locate.

So far the only writings I have from his notes are a few poems, memoranda

from the bible, the writings of

Thomas à Kempis, and quotations from many poets, political writers and speakers.

These and a mass of clippings from many sources, tracts, and pamphlets,

he called his arsenal of facts.

Father was a

mine of information on Irish history and literature, English and American

politics, and was full of reminiscences throwing light upon the building of

American railroads as far as Omaha. He

participated in two of the so called local wars between rival companies over

mining claims and railroad rights of way.

Father loathed the ward healer type of politician in the abstract, yet I

recall his being won over to a warm and lasting friendship by a country

politician in the locality; a man whom father had denounced, cursed, reviled,

and ridiculed, although never previously met.

This shrewd man realized that he had a half dozen votes in the family and

that father was an embarrassing and dangerous

piece of political artillery which could be silenced by tact and diplomacy.

Adopting these methods he won pop over, first to the extent of a

reluctant admission that although the man was in error, he was nevertheless a

lovable personality.

I have

heretofore made no reference to our family garden.

Father raised cabbage, potatoes, onions, corn, beans, and other

substantials for the family table.

Our plot being too small for the demands made upon it; he tilled some of the

then vacant lots the clearing of which provided us with most of our firewood.

Between this and mother’s economy, otherwise we though poor, were never

hungry. In addition to the animals

previously mentioned, we had flowers, rabbits, ducks, canaries, and cats.

The family cats for many years enjoyed immunity from extermination from

old Duke my boyhood dog who for fifteen years terrorized all the dogs and cats

in the neighborhood. Always hunting

and fighting, he got me into many a jam, and saved me from discipline at the

hands of my mother who dared not touch me when Duke was present.

Complaining to father about the dog , she was advised not to get Duke

down on her as he understood every word she said and would surely revenge

himself. Duke lived for fifteen

years and although old blind and deaf, tried hard to fight till the last.

Mother, although

obviously proud of father’s family, occasionally alluded to his as

The Invader.

Once, and once only father flashed back “Ah but don’t forget my dear that

the invaders landed”. Up to that

time I had been quite conceited about my illustrious lineage, but before mother

was half finished I hung my head in downright shame to think that I inherited

the blood of a marauding bunch of ruffian cut-throats who by reason of superior

numbers and greater military resources had forced themselves upon a decent

people out of the sheer lust for pillage and murder.

Later I conceived the idea of giving the younger children pennies just to

ask daddy at mealtime what year his people landed in Ireland.

Mother always bristled at this and father wisely made some meek and

evasive answer, or none at all.

On the distaff

side of father’s family I have mentioned De la Pour (Powers for short) De Burgo

(or Burke) Fitzgerald and Phelan.

John, James, Thomas, Edmond, Mary, and Ellen seem to have been

traditional family Christian names.

Contemporary relatives of my father were his cousins John and Ellen Fleming.

Unmarried, they through inheritance and business activities, amassed a

considerable fortune, the bulk of which went to charitable and religious

institutions and father and his brother received considerable sums as well.

Father’s brother John outlived him, and left his money to my brother

John, except for a thousand dollars given to my sister Mary.

Beyond question

my father was an extraordinary and splendid character in whom there were many

evidences of excellent breeding, family culture, and fine personal traits that

manifested themselves despite an untoward environment, discouraging

circumstances, and heart rendering vicissitudes.

Were I ever to attain a degree of success such as would prompt anyone to

accuse me of being a great man I would reply “Nonsense!

I am merely the offspring of two great

individuals of whom the world never heard”.

I of course enjoy the better advantages of a later generation and more

favorable circumstances. Yet in

abilities, virtue, and genuine intrinsic worth, compared to them I am but the

poor shadow of a great substance.

I have mentioned

father’s love for game fowl. While

as age advanced and his studies broadened his interest waned in many sports.

Yet he always retained a lively interest in game fowl.

In 1907, having a fine crop of young cockerels, he challenged old Billy

McMann, local veteran of the sport, to fight a farewell main between themselves,

each to condition, heel, and handle their own birds and never again to fight a

main. Billy accepted the challenge.

The fight took place in our henhouse, witnessed by many young devotees of

the sport. A splendid Lemon Pyle of

feathers broke the score and won the main for him.

The two old timers shook hands and wept.

All the young fellows seemed deeply impressed.

Billy McMann died the following year, and father about three years after

the main. His death affected father

deeply. Another incident that

occurred later upset him terribly.

A boyhood chum of his had traveled from Pittsburg to Kingston expecting to

locate father there. Failing to do

so, he wrote to their home town and getting our Rosendale address wrote father.

Father replied and endeavored to arrange a meeting.

He received word that Pat Mullins had died the previous week.

Father was in actual grief.

The Foley men mentioned elsewhere were the old country townies of father.

They and Mary Donovan of Kingston seemed the only home towners of his in

Ulster County. With these he kept

in close touch.

But for father’s

marriage, the family would now be extinct.

As it is there is to date only one grandson two granddaughters, and three

great granddaughters so though the blood may persist the name may change.

Family pride of course, prompts the desire for its perpetuation.

Yet all families lose their original identities eventually.

I regret my incapacity to do something

distinguished and enduring that would symbolize the rear guard action of a very

old family in orderly retreat from an arena which the fought for a millennium

with honor courage and distinction.

What seemed to

me father’s greatest fault was his love of an argument for argument’s sake.

In such cases he would use every device in his debater repertoire to win

his point and sidestep what was often the obvious and glaring truth.

When cornered due to something

conflicting with an previous commitment, he would squirm out of it by delivering

attacks from other directions. In

fact he could and often did justify opposite positions.

Chuck ablock with apt quotations, resorts to ridicule, hit and run

methods, and the trick of quickly attacking from another angle before the

opposition could answer the previous argument.

I could never admire that method.

In saying this I claim no superiority over my parent.

It was the way of his environment.

Formal debates then, at least locally, were knock down and drag out sort

of affairs, and decisions arrived at on a biased basis more often than approach

to facts and truth.

Father’s

European work activities included learning the baker’s trade and working in the

cotton mills of Ireland and England.

He seemed very familiar with the Manchester area in England, having

worked there for some time and returning to Ireland to participate in the Fenian

Uprising of 1867. His hometown,

Carrick On Suir was the site of Curragh More, the estate of the Marquis

of Waterford who conceded a common ancestry with father’s family from the Powers

family one of whom I believe to be my great grandmother.

The name Powers seems originally De La Poer, which is part of the

Bersford family name. Father was

quite intimate with young Lord Charles, who later became a distinguished Admiral

in the British Navy.

The mills at

Carrick were then owned by the Malcomson Brothers.

This English firm, in the expectation of receiving a cotton concession in

the South, backed the Confederacy during the Civil War and were said to help

finance the rebel privateer Alabama.

The mills at Carrick were booming during the American Civil War.

The firm went bankrupt after the Alabama was sunk by the USS Kearsarge.

This battle occurred near enough to Waterford to Induce yacht owners

there to run over to France to witness the fight.

Sentement seemed divided.

Father, unlike

most of the men of his generation, was smooth shaven most of his life though in

later years because of eye trouble, he grew a moustache.

He loved to talk to old timers and they

loved to talk to “Jimmy”, who either remembered or understood what they were

talking about. This applied in

equal force to men of all nationalities represented locally.

Listening in on many of their conversations as a child, I was variously

interested, thrilled, or terrorized according to the nature of the account.

Now nearing seventy, I fell privileged to have attended the sessions

where men born between 1800 and 1850 gathered, conversed, and related firsthand

accounts of historical events, ghost stories and many other items associated

with long, long, ago.

Psychologically

puzzling is the fact that ordinarily alert wary, and quick perceiving, father

seemed in other ways very honest minded and quite gullible.

He would trust almost anybody until they once deceived him saying “I

would rather die by treachery than pay it the respect of fear”.

Despite this, once deceived he always figuratively kept the deceiver in

front of him, often the their extreme embarrassment.

Yet as mother often said “Give him a

soft word and everything is forgiven”.

A split personality perhaps, but in how many ways?

One version of

our family’s historical background was sent to me by my Uncle John when I was a

boy. According to this account, our

ancestors fought under Strongbow during the Norman invasion of England and

Ireland in 1066. He mentioned the

family motto as being “Let The Deed Show” and the war cry as “Crom Abu” which

some claim as “Now And Forever”. My

father had only a smattering of

Gaelic and was not sure about this.

He thought that while these were part of our family heritage, he associated them

with the Geraldines or the Fitzgerald clan, whose blood entered our family via

the distaff side.

Fleming means A Native of Flanders,

those of that race that came to the British Isles during the invasion of 1066

were so called. Maureen Fleming of

Princeton, NJ author of

Elizabeth, Empress Of Austria, and

many other popular writings, mentions one Archambaud as having so distinguished

himself in the service of William The Conqueror, that he was rewarded the grant

of extensive feudal estates. His

decedents are said to have adopted the name Fleming in honor of their

illustrious ancestor having been a

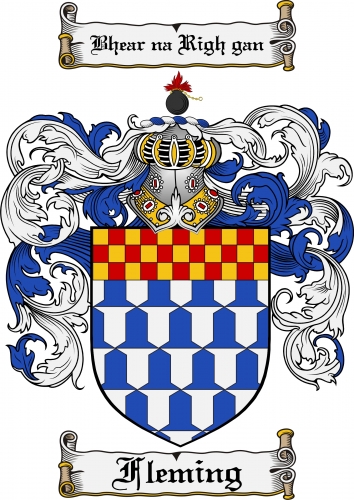

native of Flanders. Maureen Fleming’s

version of the Family Coat of Arms is a large oval shield with a smaller shield

in the center, capped by a large crown.

The greyhounds stand on their hind legs at the sides.

The ribboned motto bearing the legend

Bhear na Righ gan

(Long live the King) streams below the inner shield, and what seems to be a

section of armor appears above the crown.

Decorative designs round out a pleasing symbol cleverly engraved by

Joseph Wein.

Fleming means A Native of Flanders,

those of that race that came to the British Isles during the invasion of 1066

were so called. Maureen Fleming of

Princeton, NJ author of

Elizabeth, Empress Of Austria, and

many other popular writings, mentions one Archambaud as having so distinguished

himself in the service of William The Conqueror, that he was rewarded the grant

of extensive feudal estates. His

decedents are said to have adopted the name Fleming in honor of their

illustrious ancestor having been a

native of Flanders. Maureen Fleming’s

version of the Family Coat of Arms is a large oval shield with a smaller shield

in the center, capped by a large crown.

The greyhounds stand on their hind legs at the sides.

The ribboned motto bearing the legend

Bhear na Righ gan

(Long live the King) streams below the inner shield, and what seems to be a

section of armor appears above the crown.

Decorative designs round out a pleasing symbol cleverly engraved by

Joseph Wein.

Our family, in common with most of Irish, Scottish, and English decent spell the

family name Fleming, thereby identifying themselves as descendants of the old

invaders. Those of continental

derivation spell it Vleming. The

high hat version is spelled Flemming, which neither alters the pronunciation or

adorns an old distinguished name which spelled Fleming is associated with men of

prominence today as far back through American history.

Examples of this are: General Philip Fleming, Victor Fleming of movie

fame, Samuel Fleming founder of Flemington NJ, Sir Alex Fleming the discoverer

of penicillin, Thomas Fleming who crossed the Delaware at Trenton with George

Washington, and Marjorie Fleming.

The Man for whom Fleming County Kentucky is named (Colonel John Fleming),

and the forbearer of many Flemings throughout the South, one of whom according

to a descendent, escaped from an English penal colony in Georgia where he was

under a life sentence for his activities in an Irish rebellion.

My informant of this item was a descendant of the convict mentioned.

Although a southerner and a Protestant minister, he was far from being

ashamed of his convict ancestor who he took for granted to have been a Catholic,

adding that without doubt if his forbearers had access to the old faith, he

would have become a priest instead of a minister.

For emphasis or illustration in argument or discussion, father often cited

famous quotations from poets or writers of renown.

However when fitting he effectively, sometimes humorously, injected apt

truths commonly used by the old time Irish rank and file.

Added to these were many “nail on the head” Yankee farmer philosophies

which he admired greatly. Other

sources of his quotations included The Bible, Thomas à Kempis, Edwin Markham,

Bobbie Burns, Shakespeare, John Bunyan, Dante, Hugo, Scott, Goldsmith, Swift,

Moore, Tennyson, Longfellow, and numerous unidentified writers and thinkers.

Appropriate selections for this biography follow:

Every evil kills itself.

To turn a stream, go to its fountainhead.

Father had many recollections of the old days, ways, and people.

The first extremely dim memory was of his being attracted by the red

uniforms of a long line of men.

This was in 1848, and as supplied by his mother, the facts were: Grandfather had

gone out with the other rebels and the Red Coats came trooping up the road.

She took the children and hid in the hedge.

Father, then very young, babbled enough to be overheard and

reconnoitering soldiers located them.

Grandmother, alarmed tried to run away with the children, but to no

avail. The officer in charge told

her not to be alarmed as the British Army did not fight women and children.

He then tried to question her concerning the location of the rebels.

“Three of them stand before you sir, and the head of the family is your

match in men, and all of us are ready to die sir” she replied.

“A splendid spirit and your privilege.

Good afternoon lady” he replied then departed.

Less sportsmanlike however, is an exchange of retorts to a great English Prime

Minister, who according to one of Father’s stories, visited the local school

then instructed by a Scottish teacher.

Sir Robert Peel, in questioning some of the older boys asked: “When was

Ireland joined to England?” An

alert Irish lad replied that it never had been.

“You are a stupid fellow.” Growled Peel.

“It is you that is stupid sir” replied the youth.

“Don’t you know that the Channel runs between them?”

Quite so Jackanapes, quite so.” replied Peel.

“I wonder if you can tell me when Ireland was conquered by England?”

“It never was and it never will be!”

shouted the boy. Other half

grown lads took up the shout and Sir Robert walked out in a huff to the

mortification of the teacher who ordinarily had his hands full with the big

boys. Commenting on the incident

later, father thought Peel not only ignorant of the conceded privilege of the

Irish soldiers to curse the Queen and fight for her.

Peel, claimed father, “looked for trouble and found it, or at least

underestimated the Irish intelligence, a mistake that but very few British army

officers make.

Relevant here is the remark that I was well acquainted with two former life

guards of Queen Victoria, both of these often hummed or chanted certain

vulgarisms anent “The Quane” but would fight with anyone else who would say

anything against her. Both men were

Irish and about 6ft 3in tall. Noble

looking but hard drinking ne’er do wells.

Each admitted getting kicked out of the regiment after Victoria had over

ruled several previous charges against them.

They claimed Victoria knew most of her men by name and was very kindly.

From his working years in England, father got many good impressions of the

English common people, and never at any time spoke ill of them.

One story concerning an incident that occurred in Manchester points to a

commendable sportsmanship existent there.

The Irish in that city then were few in number.

A dog fight had been arranged between the Irish and English dog fanciers.

During the event, one hot headed Irishman let his dog out and boasted

that it could whip any dog in England, and that he personally could whip and man

in England. A very calm voice

immediately advised him not to make any bets on his brag as there were at least

three Englishmen present that could easily whip him, and speaking for himself,

he thought he could too. The Irish

dog did win but neither its owner nor any of the Irish present offered any bets

on the fellow himself.

Despite favorable opinions of the English common people, father always opposed

its government claiming that only the aristocracy actually benefited from it,

and the lot of the poor was almost as bad as it was in Ireland.

He frequently pointed to a national debt that they could never pay, yet

luxury existed side by side with poverty and squalor.

Dry rot, time, and human progress he averred would actually destroy The

Empire. Illustrative of his attitude

towards the British Government is contained in an account of his introduction to

a brickyard where he first worked in America.

“Immense pikes of brick everywhere and more in the process of

manufacture” He often mused, adding “and the British Army thousands of miles

away from me and these other Irish lads.”

Aside from the humor of this story, there is also a pathos.

He was one of many brave Irish lads who was only recently routed in a

quickly suppressed rebellion. This

was due largely to the lack of proper equipment.

Their chief dependence being contraband pikes made surreptitiously in

parts thrown into the river from local English owned factories by rebel

mechanical workers there (Carrick at least) and picked up by awaiting Fenian

members along the banks of the Suir

for distribution to other comrades.

What wonder then, that at least one of them who shortly afterwards (1869) faced

with a vast amount of potential fighting material would intelligently discern

its possibilities under favorable circumstances.

The Fenian uprising in 1867 was quickly suppressed due to many factors.

Father’s group never contacted the enemy.

Except for pikes, they had very few weapons.

He always claimed that the rising was premature.

They took to the field in early March and were out in the open

unprotected in the heaviest snowstorm the locality experienced in many years.

Poorly clad, unsheltered, lacking arms and other supplies, hungry and

cold, they were relieved when the order came to disband.

While in the field, he and others received the sacraments of Confession

and Holy Communion from the monks at Mount St. Melleray Monastery.

His French confessor there, aware of father’s rebel status, advised him

to keep constantly in the state of grace and be ready to face God.

A similar account of a like occasion was given to me by a brother of my

mother (William O’Sullivan 1853 - 1939).

This uncle was a rebel in 1867, but was a Clogheen County Tipperary

native. Mount St. Melleray I

believe, is not far from the birthplace of either of my parents.

The Fenian uprising in 1867 was quickly suppressed due to many factors.

Father’s group never contacted the enemy.

Except for pikes, they had very few weapons.

He always claimed that the rising was premature.

They took to the field in early March and were out in the open

unprotected in the heaviest snowstorm the locality experienced in many years.

Poorly clad, unsheltered, lacking arms and other supplies, hungry and

cold, they were relieved when the order came to disband.

While in the field, he and others received the sacraments of Confession

and Holy Communion from the monks at Mount St. Melleray Monastery.

His French confessor there, aware of father’s rebel status, advised him

to keep constantly in the state of grace and be ready to face God.

A similar account of a like occasion was given to me by a brother of my

mother (William O’Sullivan 1853 - 1939).

This uncle was a rebel in 1867, but was a Clogheen County Tipperary

native. Mount St. Melleray I

believe, is not far from the birthplace of either of my parents.

Mount St. Melleray Monastery

Father had an interesting story concerning the early history of Mount St.

Melleray and it ran thus: Founded

by the French monks by permission of the owner, they through thoroughly hard

work, converted a valueless mountain area into fertile fields and gardens.

A later landlord is said to have insisted on reclaiming the land.

A lawyer said to have been Daniele O’Connor interceded and got either a

deed or a stay in proceeding until “Tomorrow”.

Fact or fiction I know not.

Neither did my father.

Father often made mention of local fools.

I recall his claiming to have seen two of these “unfortunates” in close

conversation, and seeming to understand each other’s gibberish.

Other apparent fools he designated rouges in masquerade who assumed their

role to win sympathy and avoid work.

One of these stories concerned three of the latter type.

One of these had attached himself to the Marquis of Waterford’s estate

and was enjoying all the immunity of his privileged status.

Along came a town fool who also tried to entrench himself on the

property. The other fool beat him

off. The beaten fool returned to

town and later returned with a third fool who soundly thrashed the estate fool.

Seeing the fight the Marquis ordered them separated and asked the strange

fool “What are you beating my fool for?”

“Because he bate my fool!”

Carrick seems even in those remote days, to have many characters the counterpart

of whom is yet to be found in big and small settlements, perhaps everywhere.

Easily recognizable to me is Mile

A Minute a dignifies snail paced gentleman who when enraged when being

called by his nickname, often outran many a fresh Carrick boy and slapped him

into more respectful behavior.

Familiar too is the old time Sanctified

Joney, an incessant pesterer of the clergy and also a malicious local

newsmonger, who piously renounced the sin of the scandals she peddled.

Charitable as the Irish are towards the

dead, when Joney died the neighbors

softened their opinion that though she surely went to hell, she was there

without sin.

Among his other recollections, father claimed to have conversed with a very old

lady who told him that she saw her father and her thirteen brothers drop their

work in the fields and rush off to the battle of Vinegar Hill in 1798.

I believe the claimed that they all perished in that battle, but as I am

recalling the item from statements made fifty years back, I am not sure.

In interesting too is a story father told of an 1866 encounter with a man

purportedly to be 104 years old, who bet him a ha’pence that he could beat

father in a dash across the rathad (road).

The old man won the bet too, and father gave him a shilling.

Learning that father intended going to America, the old man informed him

that he too once started for New York.

He sailed in “Boney’s time” (during the Napoleonic Wars)

but the ship was captured by the French, and he did not get back to Ireland

until after the war.

Father remembered The Crimean War quite well, and knew personally various of the

men who fought in its battles. I

often heard him refer to The Malakoff, The Redan, Sevastopol,

and Balaclava in connection with some of the veterans he knew.

Crimea seems to have taken a rather heavy toll in his locality, as I

remember him relating details about “The Kiln Boys” of the region.

These were a tough bunch of fellows, who in the early 1850’s used to

gather on cold evenings around a local Lime Kiln to drink fight and carouse.

They stole and roasted local lambs and poultry for their feasts, and were

a neighborhood problem and worry until the Crimean trouble broke out in 1854

when most of them enlisted. None of

these to my father’s knowledge ever returned to Carrick.

I

have frequently alluded to Carrick as my father’s native village.

As there seem to be quite a few Carricks in Ireland, I should qualify by

stating the father was born somewhere in County Waterford, perhaps Portlaw or

Carrick, Carrick Beg, or Carrick on Suir, which lacking an atlas I cannot

pinpoint. I remember father

mentioning that it was just a nice Sunday walk into the city of Waterford City,

a walk which he frequently made. In

regard to Waterford City, I remember him saying something about Strongbow’s

Tower being there. It is my

understanding that the Norman invasion of southern Ireland was under the

direction of Strongbow. Under him I

believe fought the Flemish crossbow men.

One of these was my ancestor.

Intending to file a few copies of this family history in the Waterford

area, I add for identification purposes, that until about 1912 my Uncle John

Fleming lived part of the time in County Waterford at Portlaw, and sometimes in

Droylsden near Manchester England. Up

until his decease, he had cousins living in and around Carrick.

These were named Conoway. Of

a later generation, I recall something about a certain Dean Henneberry. Two

other cousins predeceased my uncle.

These were a John and Ellen Fleming.

Similar identifying data elsewhere in this book will I hope support many

claims and statements therein.

During the early years in America, father knew and conversed freely with the

veterans of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War.

Among his fellow workers were many Civil War Veterans.

He thus had a good knowledge of many famous battles.

Many Irish participated in the Civil War.

Some as citizens, others as volunteers, and still others as substitutes

for drafted men. A few local men

served in The Confederacy due to their being in the South at the outbreak of the

war.. A story of father’s concerns a

greenhorn Irishman who for $500 agreed to substitute in the war for a local

businessman.. For the fee of it, his

army commander convinced him that a bounty was also paid for every rebel soldier

killed.. Shortly after reaching the

war front, they were called out hurriedly to reinforce another outfit..

“How many rebels are out there?” inquired the Irishman..

“Oh golly Pat, there’s a million of them.””

a jokester said.. “Praise be

to God!! Me fortune is made.””

Averred the greenhorn..

Strongbow’s Tower Waterford, Co. Waterford Ireland

During the early years in America, father knew and conversed freely with the

veterans of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War.

Among his fellow workers were many Civil War Veterans.

He thus had a good knowledge of many famous battles.

Many Irish participated in the Civil War.

Some as citizens, others as volunteers, and still others as substitutes

for drafted men. A few local men

served in The Confederacy due to their being in the South at the outbreak of the

war. A story of father’s concerns a

greenhorn Irishman who for $500 agreed to substitute in the war for a local

businessman. For the fee of it, his

army commander convinced him that a bounty was also paid for every rebel soldier

killed. Shortly after reaching the

war front, they were called out hurriedly to reinforce another outfit.

“How many rebels are out there?” inquired the Irishman.

“Oh golly Pat, there’s a million of them.”

a jokester said. “Praise be

to God! Me fortune is made.”

averred the greenhorn.

Among our family stories are the following.

My grandmother’s brother The Reverend Edmond Phelan, a Catholic priest

had a guest one day who in the course of conversation revealed himself as an out

and out atheist. On discerning

this, Father Phelan called to his housekeeper saying “Lock up the silver Katie,

and leave nothing of value around.

This man don’t believe in God.”

Another story relates to an ancestor named Phadrig, a man in good circumstance

and something of a duelist. One day

while dinning in London, he was surprised to uncover a platter of potatoes,

boiled with their jackets on.

Titters from an adjoining table emphasized the inference.

Phadrig said nothing but ate the potatoes in apparent relish.

Recognizing those who tittered as regular hotel guests, he bribed (as

they seemed to have) the waiter to put a large platter on their table.

When it was uncovered it revealed one of Phadrig’s cards for each man at

the table. To each card was added:

At dawn, at your pleasure.

The wags left the hotel rapidly.

Another facet of father’s character is revealed in the following story.

He had been idle all winter of 1881-1882.

Shortly after work was resumed the following spring, he was seized with

malarial fever and ran deeper into debt.

Believing father was going to die, the grocer cut off our provisions.

Ten years afterward father walked into the grocery and threw the money he

owed on the counter saying “I didn’t die, or any of my family either but no

thanks to you Hank.” The grocer

admitted to me twenty years later that he had been sure father was going to die

and he was really surprised and ashamed when the bill was finally paid.

Great grandfather is said to have been a builder who retiring, invested in farm

lands. Intelligent whole souled and

honest minded, he was victimized and robbed by those in whom he reposed

confidence. One rascally farm

overseer is said to have sold off choice beef cattle and reporting them as dying

of disease. On hearing of the loss,

the old man would tell the overseer not to worry adding “Let us thank God it is

not our overseer or any of our families”.

Great grandmother however was not so gullible and her subsequent

investigations resulted in the overseer’s dismissal.

Two railroading chums of father’s during his first years in America were named

Norris and Noonan. Once applying

for work in Illinois the foreman, a Yankee named Nickerson, told them that none

of them looked to be much of a man, and that he would only have to beat them up

three or four times a day to get enough work out of them.

“Sir” replied Norris, “I am the worst man of the three.

Now if I can lick you, would that prove anything sir?”

Get the hell in there and carry them rails, and no back talk or I’ll

knock the daylights out of all three of you” roared the foreman.

Other of Father’s stories relate to a wise fool or “cuteen” who asked my

father to hold a roll of bills for him overnight and next day he claimed he was

ten dollars short. A brickyard

story tells of an Irishman who on entering a company shack or boardinghouse

warned all “Far Downs” or Northern Irish to leave or prepare their souls for

eternity. Also there is a story

that relates of a fellow who prayed loud and long at his bunk side every night,

with a pile of bricks beside him.

These he would hurl in any direction from whence came a protest, comment, slur,

or titter.

Concerning an old country experience, father told of a visit to an Irish fair

while the spirit of old coat dragging and shillala waving faction challenges

still smoldered. The Waterford boys

were approached by a friendly chap who inquired where they were from and who was

their best man. When told, he said

he was from one of a group from Tipperary “all good men and out for sport.

Come on over and join us”.

They went, and after an informal introduction, the Tipp called one of his gang

saying “This is a fine man, but he is getting tired of beating up Kilkenny lads

and would like to try his luck on a Waterford lad.

Are any of ye worth your salt?”

This was too much and a general fight started which left all the

participants bearing scars of the battle.

This experience was the basis of father’s claim that some men never learn

by experiences; however he never made that claim within hearing of my

intelligent Tipperary mother.

A racing fan himself, father admired the spirited Irish and English horses.

If I remember correctly, he was a friend of a great Irish jockey (John

Ryan ?) said to have been a derby rider, perhaps a winner.

Father’s comment on the frequent teaming up of stallions for work

purposes in America was “Never the like of it ever be tried in

aither Ireland or England”.

Pastured bulls also puzzled him as Irish bulls were terrible he said.

Father’s game cocks and dogs were well bred gamey animals.

When cross bred at all the combination proved to be an improvement.

Before I ever saw an Airedale or Bullterrier, he was crossing terriers

and bulldogs to obtain quick, strong, gamey dogs and never got excited when the

expected occurred between them. I

recall my eldest brother, who was then working away from home, bringing back a

splendid fox terrier. Father was

reading when Jim entered with the fox terrier.

My boyhood dog throttled the interloper at once.

Mother fled with an infant child and I felt none too brave myself.

Father removed his spectacles and asked my brother to separate the dogs.

This done, father asked quietly “Where did you get him Jimmy?”

Given the details, his comment was “He is a game little divil, but too

light for owld Duke , though he is younger.

He will learn though. But we

are going to have a divil of a time getting them used to each other”.

As a character, my father had many of the better traits of Bobby Burns and

somewhat paralleled Wilkes Micawber as he seemed always denouncing smart

practice and unethical procedures.

I remember him quoting from Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical on labor in one of

his arguments adding “Compare that sir to the conceit of well fed and over

privileged individuals who believe that some are born to rule and others to be

ruled, and consider themselves one of the Lord’s chosen”.

Temperate and hardworking, he was a popular neighbor among mixed

nationalities, and seemed something of an advisor or confessor to many workman.

Once, due to a work incident, an illiterate backwoods Yankee called to discuss

it with my father. An old man was

seen kneeling and praying alongside of his work.

The backwoodsman called father’s attention to it.

Father came, looked, and then tiptoed away beckoning the Yankee to do the

same. “Wasn’t that nice Jimmie?

What was he doing?” asked

the backwoodsman. Told that the old

man was praying to God, the big fellow wistfully remarked that he wished that he

knew something about God as he had lots of worries that nobody else cared a damn

about and he never learned to pray.

Father sent him to the Episcopal Minister mentioned elsewhere in the book.

Father

had many friends among the German folk, and the later coming Slavs, Polish and

Italians. Only a few Jews lived in

the neighborhood. These were mostly

businessmen. Despised by many,

traded with by nearly everyone, they were hated by their competitors of other

nationalities. Father claimed that

Jews simply had to be shrewd to avoid extermination.

He often said “The Galilean was a Jew.

He loved, forgave and prayed even for those who crucified him, and who

are we to gainsay him”. As a dog,

pigeon, and game fancier, father was admired by the old timers and beginners

alike in each of these sports. He

could have his pick of their best stock gratis.

One pigeon breeder, a winner of hundreds of exhibit prizes, once remarked

to me that father being the last of the old time fanciers “could have anything

I’ve got, anytime, for the taking”.

Religiously he attended Sunday Mass regularly, went to confession every

Christmas and Easter, his devotions otherwise consisted of religious reading,

chiefly his prayer book and his all beloved Imitation of Christ.

As a father he was Kindly, tolerant,

lenient, and quick to forgive. He

disliked seeing mother punish us.

He loved to fondle and amuse small children.

I remember one night he showed me how to thumb twiddle, and promised to

later show me another way of doing it.

Eager to learn, I pestered him until he did it in reverse.

He had a lot of child amusing tricks, songs, and stories, and among the

few jingles I dimly recall were the “Four and Twenty Blackbirds” and the trick

accompanied “Go to bed, go to bed

Tom”. Believing over education to

be at the root of much discontent, he approved of it only to the extent of an

individual’s capacity to absorb and utilize it.

Once when brother Tom weeping bitterly, protested against being educated,

father said to mother “That child has the sense of

Wiseman. Maybe we are

raising a “janious”. Personally I

feel sure Tom would have made his mark had he not been claimed as a war casualty

in 1918.

By heredity, father claimed, Flemish, Norman, Danish, Irish, and the Geraldine’s

Italian blood. My mother, a

Tipperary O’Sullivan, claimed that a great grandmother of hers bore the English

name of Spottswood. The third

American born generation have variously infusions of Dutch, German, and American

blood. Of these, as of 1949, there

is only one male. There seems to be a

celibate streak in our family, as father was the only one in his generation who

married. Of his children only two

sons married. In his grandchildren

however, the tendency seems to marry young.

Virtually the last of his line, father chose mother to perpetuate his

family and buttress attributes they already possessed; an infusion that matched

his own blood, producing excellent offspring.

Often when facing situations which would have trapped my hot-headed father, my

mother’s influence has saved me by recalling some of her repeated warnings: “Put

yourself in no one ones power” or “When you have you hand in a dogs mouth, draw

it out as aisy as you can”. For me,

their like, similar, and unlike characteristics were fortuitous.

They shared and endured a poverty of material things and may in the eyes

of the world be adjudged failures, yet in the worthwhile and praiseworthy things

of the soul and character, they were rich and successful.

Colossal memorials have been built commemorating fools, tyrants,

butchers, murderers and mediocrities, while billions of just and honorable world

builders sleep forgotten. Reasoning

these, I share views variously and beautifully expressed by Bobbie Burns, Thomas

Grey, Edwin Markham and others.

Born in an historic period, father witnessed the transition of things from the

old order to the new. His father

never saw a railroad, though father aided in the building of many.

He saw the development and expansion of steam power, photography, the

telegraph, telephone, electric power, phonographs, radio, airplane, automobiles,

harvesting machines, gas driven engines, the X-ray, improved production methods,

and a thousand other things which made for world betterment.

Claiming that he had been born a hundred years too soon, and he

prophesized that the time would come when most of the world’s work would be done

by machinery, and all mankind would have ample food, clothing, comfort, and

leisure.

Although a staunch laborite, he did not view labor saving devices with alarm,

claiming that although they displaced labor, they saved lives and would force

government responsibility for the unemployed, and measures regulating fair labor

distribution. He pointed that

hammer and jumper hand mining had sent many miners to an early grave, and gave

easier jobs to those who replaced them.

He claimed that the harvesting machines earlier destroyed by angry

English peasants, were the forerunners of those that made possible the

development of our western wheat empire.

Once seeing an automobile with glaring headlights pass our house one

night he commented “Byes oh byes.

If that blasted thing had appeared anywhere in Ireland fifty years ago, there’d

be a scared Irish family at the top of every tree on the island”.

Well versed in history, his reminiscences, and those with whom he loved to

converse , were replete with incidents associated with important events of long

ago. His own father as a young man,

fought for Belgian independence in 1829 with Thomas Frances Magher, and later

participated in the Irish rising of 1848.

It is also claimed that a younger brother of my grandfather served in

Meagher’s Irish Brigade during the American Civil War.

Father had conversed with the men who had served throughout the Crimean

War. He likewise talked with

veterans who fought in India during the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857.

Several of these claimed to have seen Old Nana Sahib, The Butcher of

Cawnpore.

During the public readings of the Civil War News, father met two interesting

local characters. One of these

known as Mickey Mixup, was as his nickname implied, prone to getting things

wrong. In relaying the news, Mickey

would proclaim that the United States was knocking the hell out of the

Northerners, and Lee’s men were chasing the rebels from pillar to post.

Another regular attendant of these readings was an elderly poorly clad

yet dignified looking old farmhand from a nearby gentleman’s estate.

Having heard this man being referred to

as a Poor Scholar father made it a

point to get acquainted with him.

He found that the man, though wholly illiterate, could repeat accurately every

item he heard read from the newspaper.

His English was accurate and grammatical in imitation of the schoolmaster

who made public the news dispatches, supplemented by his observably close

attention of the Sunday sermons of the parish priest.

Irish however was the man’s mother tongue, and according to father in it

he was eloquent. This was

manifested by his acting as an interpreter for many interested older folks whose

knowledge of English was limited.

The Poor Scholar seemed effortlessly able to translate rapidly from English into

Gaelic and hold the interest and attention of the Irish speaking elements to the

outspoken admiration of the gentlemanly English born local pedagogue.

The Poor Scholars of Ireland in the Black

Centuries seem the spiritual descendants of the ancient bards.

The scholars went from house to house

and taught Irish children for centuries receiving little more than their bed and

board in worldly recompense, yet in the intangibles their gains were priceless.

They helped keep alive the Gaelic tongue, learned the rudiments of

education and taught them to others who passed them on to others who preserved

the national spirit, and inch by inch after many centuries, regained for Ireland

a rightful place among the nations of the world.

Interesting too that father visited the Lakes of Killarney, The Vale of Avoca,

the cities of Dublin, Cork, Limerick, and other famed Irish localities.

He was told that a walking stick laid on

the ground at evening in The Vail of Avoca, would be covered with grass in the

morning. He never claimed to have

kissed the Blarney Stone. His

attitude was that no Irish born person needed to acquire fluency.

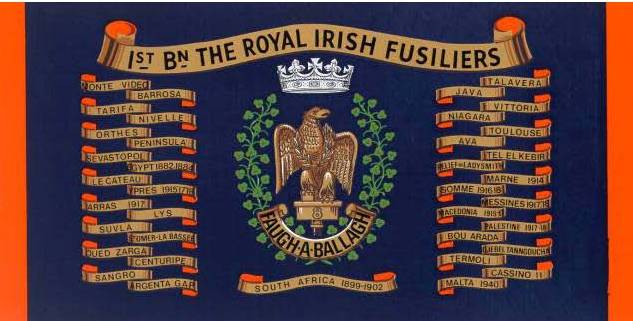

He once told me of seeing an Irish regiment who wore three sleeves on their coat

in in commemoration of having turned the tide of a long ago continental battle

by rushing to the battlefield half-dressed and making a magnificent charge.

A former blacksmith and fellow townsman

of O’Donovan Rosa, informed me that the regiment mentioned were known as the

Faugh A Ballagh which I think means either Clear the Road or Keep Out Of Our Way

(More accurately, “Clear The

Way”-

Tipp) My father also told of another

battle in which Irish soldiers turned the tide.

An Austrian Prince Eugene is said to have been in command of enemy

forces. His forces seemed to have

captured the commanding officers of the opposing army.

Prince Eugene is said to have had this officer brought to headquarters

for a talk during which Prince Eugen pointed out the futility of further

resistance against him as the battle was already won except for a last ditch

effort by a wild Irish regiment who were merely committing suicide.

He pleaded for the immediate recall of these brave foolish men for whom

there was no hope. The captured

officer suspecting the Prince, refused to issue the order.

Prince Eugene angrily turned away and shouted “To Horse!

To Horse!” and in a half hours’

time his army was in full retreat.

A similar story told by my father, related to Napoleon’s Old Guard.

These brave Frenchman shown the futility of resistance are said to have

answered a request to surrender in the immortal words “The Old Guard Dies!”

Way”-

Tipp) My father also told of another

battle in which Irish soldiers turned the tide.

An Austrian Prince Eugene is said to have been in command of enemy

forces. His forces seemed to have

captured the commanding officers of the opposing army.

Prince Eugene is said to have had this officer brought to headquarters

for a talk during which Prince Eugen pointed out the futility of further

resistance against him as the battle was already won except for a last ditch

effort by a wild Irish regiment who were merely committing suicide.

He pleaded for the immediate recall of these brave foolish men for whom

there was no hope. The captured

officer suspecting the Prince, refused to issue the order.

Prince Eugene angrily turned away and shouted “To Horse!

To Horse!” and in a half hours’

time his army was in full retreat.

A similar story told by my father, related to Napoleon’s Old Guard.

These brave Frenchman shown the futility of resistance are said to have

answered a request to surrender in the immortal words “The Old Guard Dies!”

Thomas Moore - Irish Melodies, Volume 6

| Oh, where's the slave so lowly, Condemn'd to chains unholy, Who, could he burst His bonds at first, Would pine beneath them slowly? What soul, whose wrongs degrade it, Would wait till time decay'd it, When thus its wing At once may spring To the throne of Him who made it? Chorus: Farewell, Erin, - farewell, all, Who live to weep our fall! |

2. Less dear the laurel growing, Alive, untouch'd and blowing, Than that whose braid Is pluckd to shade The brows with victory glowing. We tread the land that bore us, Her green flag glitters o'er us, The friends we've tried Are by our side, And the foe we hate before us. Chorus: Farewell, Erin, - farewell, all, Who live to weep our fall! |

The other story related to O’Connell pausing and searching in his pocket

in front of a then well-known beggar woman who opened up on O’Connell thus:

“ Oh sir, may the blessings of God follow you morning noon and night, all

the days of your life. O’Connell

put a toothpick in his mouth and slowly walked away.

The disappointed beggar lady shouted after him “And may it never overtake

you”. Highly pleased, O’Connell

returned and gave her a Sovereign saying “Now my good woman, I want you to curse

me please”. The beggar looked at

the Sovereign and then at O’Connell and replied “Oh kind sir I can’t curse you,

but the curse of God on you!” Vague

in my memory is another story associated with O’Connell, who whether because of

a wager or some other purpose, caused a single Lucifer match or flame to

indirectly light every fire in Erin.

This was accomplished perhaps by the original flame being passed by hand

from house to house or by less direct means spurred on by a prevalent belief

that the end of the world was imminent and that all who kept a fire kindled from

the flame of a widely circulated candle, would be spared.

Clearer in my memory is a description of a chronic “God help me” or pessimist

who seemed always crestfallen and depressed.

Something of a poet, this fellow incessantly murmured his woes to himself

bystanders regardless. Oh, oh, oh,

the shadow is on me. Woe, woe, woe.

Oh, oh, oh, I was born for misfortune.

Woe, woe, woe”. Brief was

the story of a peasant woman who had one hen.

When the hen laid an egg, the woman would rush off to town and sell it

for a penny. When reminded that she

had to pay a ha’pence each way at the toll gate she replied “Oh anything so as

to be in the trading line”. Another

mentions a slowpoke townsman, Stoop

shouldered and slow of gait, he was known as “Here’s me head and me behind is

coming”.

Father claimed that a bat had no classification other than its name in the

animal kingdom, as it is neither bird nor beast.

How this came to be is related in one of his stories:

Once upon a time the birds and the beasts had a terrible war between

them. During it, the bat perched

along the sidelines cheering the respective gains on both sides.

“Hurrah, hurrah for our side,

I’m a bird” he would shout when the birds had the advantage.

Then “Hurrah, hurrah, for our side.

I’m a beast” he would scream when the beasts seemed to have the upper

hand. A wise old elephant with a

good memory called for a truce.

Discussion followed during which many on both sides recalled that the bat had

ardently promoted the war among both classifications.

Peace followed, and both sides repudiated all relationship with the bat

species who according to their verdict was “neither bird nor beast”.

Apparently mountebanks were as clever and suckers were as gullible in olden

times as they are today.

Illustrative of this is father’s account of a faker who cleaned up at a Kilkenny

fair exhibiting a horse with his head where his tail should be and vice versa.

Some of those duped felt too ashamed to expose the fraud, and others

humorously recommended the spectacle to their friends, who in turn praised it to

others. Thus did an old horse

harnessed to a wagon backwards become a profitable attraction.

Tom Pepper is said to have been a notorious liar, trouble maker, and general

nuisance. Tom was chased out of

hell for being a common disturber.

According to the story, the devil ordered Tom brought to headquarters.

“Pepper” said the devil, “everybody knows what kind of a place we keep

here and the types we cater to. I

admit we ain’t much, yet in a way we have standards beyond which I refuse to

sink. You have been here only a

month, yet in that time you have made more trouble than my toughest guests.

Get out!” “But” replied Tom,

“What will I do? They won’t have me

in Purgatory or Heaven. So where

can I go?” I don’t care where you

go or what happens to you as long as you keep the hell away from Hell” said the

devil adding, “But hold on a minute.

Blast it, you’re no good to me yet you can be of service to me.

There is too much peace in the world today, and it’s on the increase.

That’s bad for my business. I

need sinners so I’ll make ye me agent and send you back to earth to drum up

trade for me. I know better than to

trust you but I also know that you are of no good whatsoever.

So whatever you do on earth is bound to help me.

So back you go tonight , and under no circumstances must you ever come

here again. Get out!”

The Irish in my home town comprised of individuals from various parts of

Ireland. We had many Corkonians, a

few Far Downs, several Waterford families, an occasional Tipp, and a scattering

from Mayo, Donegal, Kilkenny, and other counties.

The brogue of each section differed, otherwise they seemed typical Gaels.

Save for a pardonable clannishness towards their home towns, they were

ordinarily friendly to all. Yet

when quarrels broke out, the first insult they offered would be a reflection on

the other fellows home county. Many

Country Borns of the first American

born generation seemed similarly prejudiced.

Some of the latter were much older than my father, a few of their

forbearers having come to America as early as 1800, and after 1824 others came

to our locality in the hundreds.

For

well over a century American born Irish have been intermarrying with American,

German, Italian, Polish, and other nationalities.

Due to the heavy waves of immigration from Germany contemporary with

similar waves from Ireland a century ago, the preponderance of the earlier

intermarriages were amongst the Irish and Germans.

Intermarriage and close association influenced alike the successive

rising generations to a point that prompted my father to say of them “Dutch,

Irish, or Yankee, they are all alike”.

This in contrast to all the characteristics of the pure bred elements

which differed greatly as is illustrated by another of father’s assertions.

“A drunken German likes to laugh and sing, Yankees want to fall asleep,

and Irishmen want to pick a fight”.

In this connection he claimed that neither the Irish nor the Indians knew how to

handle liquor.

In common with many other nationalities, some of the Irish drank not wisely but

well. A few I recall , kept bone

dry for long periods and then went off on a bender which lasted as long as their

money held out. A portent of a

forthcoming spree on the part of one man was his donning of a heavy overcoat

regardless of the season. In this

he slept wherever he fell. Such a

spree often brought on the “fancies”, and the ailing addict would be with the

fairies for some time. On one such

occasion, the frightened wife of a man thus afflicted called a neighbor who was

an authority on such matters. This

veteran of many such bouts with John Barleycorn consoled and instructed the

wife, and then left for the village where he spread the rumor of the victim’s

death. As this happened on a Sunday

morning, dozens of Irish villagers called at the house of the purportedly

deceased man. Among these were some

very old women. Adept keeners, they

marched into the house wailing and lamenting loudly.

The invalid jumped out of bed and demanded to know what the hell was

going on. The stream of mourners

fled panic stricken, some of the older ones outstripping all others into the

village. When later accused of

rumor mongering, the responsible individual claimed that he meant that the other

fellow was “dead drunk”.

The custom of waking the deceased neighbors prevailed among the Irish for many

years. Originally marked by the

unseemly faults of earlier times, these gradually modified until nowadays they

give little cause for criticism. I

recall many of the old fashioned wakes and have observed some of the old time

keeners lamenting the deceased in Gaelic.

I adjudged these to be both picturesque and impressive.

I likewise admired the charity that forbade peaking ill of the dead even

when little else could be said concerning the departed soul.

I remember the wake of one such individual who was generally and