Articles:

The Astor Place Riots

May 10 1849

Old Stuyvesant Street

Navigating The 1950 US Census

Michael Collins - Portrait by Sir John Lavery

St. Conall Cael's Bell Shrine

| The Family News Letter Vol. 8 |

|

Articles:

The Astor Place Riots May 10 1849

Old Stuyvesant Street

Navigating The 1950 US Census |

Michael Collins - Portrait by Sir John Lavery |

St. Conall Cael's Bell Shrine |

The Astor Place Riots May 10, 1849

Something Wicked This Way Comes (The Forrest - McReady Showdown)

|

Edwin Forrest William Charles McReady |

The Astor Place Riot of 1849 is a significant event in American history that

highlights the intersection of class conflict, cultural tensions, and popular

entertainment. Occurring on May 10, 1849, in New York City, the riot erupted

outside the Astor Place Opera House and resulted in the death of at least 25

people, with over 120 injured. This incident not only underscores the intense

class antagonism of the era but also reflects the cultural dynamics of a rapidly

changing society.

The immediate cause of the riot was Macready's performance of Macbeth at the

Astor Place Opera House, a venue associated with New York’s elite. Forrest's

supporters, largely from the working-class and immigrant communities, viewed

Macready as a symbol of British cultural dominance and aristocratic pretension.

On the night of May 10th, tensions boiled over as thousands of Forrest

supporters gathered outside the opera house, protesting Macready’s performance.

The crowd, driven by a mix of national pride and class resentment, clashed

violently with the police and the militia, resulting in a deadly confrontation.

In addition to class tensions, the riot also reflected the nativist sentiment

prevalent in the United States at the time. Many of Forrest's supporters were

Irish immigrants who faced discrimination and hostility from native-born

Americans. The riot, therefore, was also a manifestation of ethnic and

nationalistic tensions, with Forrest’s supporters rallying against what they

perceived as an imposition of British cultural values.

Stuyvesant Street

Astor

Place formerly Stuyvesant Street, is a truncated road that intersects Lafayette

and Cooper Streets ending at Third Avenue once extended all the way to the Peter

Stuyvesant estate by the East River.

The road runs contrary to the grid in true east west orientation and was laid

out in 1787 by Petrus Stuyvesant the great grandson of Peter Stuyvesant.

Before 1860 Astor Street was known as Stuyvesant Street and Peter

Stuyvesant's farm was adjacent to St Mark's Church of which he was a Patron.

By the 1850s the city was relentlessly moving northward and property owners were

coming under increasing pressure to sell to developers. The Stuvesant

properties were sold, St Marks Cemetery on Second Avenue between Eleventh

and Twelfth Streets was closed and the bodies disinterred and moved. The

sole remaining property from that era is the Stuyvesant Fish House built in 1795 is located at 21

Stuyvesant Street.

Astor

Place formerly Stuyvesant Street, is a truncated road that intersects Lafayette

and Cooper Streets ending at Third Avenue once extended all the way to the Peter

Stuyvesant estate by the East River.

The road runs contrary to the grid in true east west orientation and was laid

out in 1787 by Petrus Stuyvesant the great grandson of Peter Stuyvesant.

Before 1860 Astor Street was known as Stuyvesant Street and Peter

Stuyvesant's farm was adjacent to St Mark's Church of which he was a Patron.

By the 1850s the city was relentlessly moving northward and property owners were

coming under increasing pressure to sell to developers. The Stuvesant

properties were sold, St Marks Cemetery on Second Avenue between Eleventh

and Twelfth Streets was closed and the bodies disinterred and moved. The

sole remaining property from that era is the Stuyvesant Fish House built in 1795 is located at 21

Stuyvesant Street.

Above: Fish Hamilton House

The Opera House

The Astor Place Opera House built in 1849 was situated on a wedge shaped piece of land that is between Broadway on the west and Lafayette Street on the east. and Astor Place to the south. The Opera House was completed in 1847 and opened in November of that year under the management of Edward Fry. It was conceived as a performance center for opera which appealed to the wealthy or upper ten per cent. Verdi's works were featured in the first two season and were well received, but the receipts were not sufficient to sustain the theater. In 1849 it was therefore decided to stage Shakespearian performances and the renowned English actor William Macready was engaged to perform MacBeth. New York City at the time was experiencing an unprecidentd influx of immigrants, primarily poor Irish which had fled the repression in their homeland and most recently the deadly famine. Those factors as well as anti Irish sentiment by nativists would combine to make a deadly brew that would become an even costlier prelude of things to come.

8th Street/Street/St. Marks Place: New York Songlines (nysonglines.com) The location of the former Astor Place Opera House as it appears today. Songlines NYC Website

Left: Clinton Hall formerly The Astor Place Opera House photographed in 1875

8th Street/Street/St. Marks Place: New York Songlines (nysonglines.com) The location of the former Astor Place Opera House as it appears today. Songlines NYC Website

Right: The William Perris New York City Ward Map of 1852 depicting the area bordered by University Place to the west, Forth Avenue to the east, Shortly after the Astor Place Riots in 1849, the Astor Opera House which was the scene of one of the deadliest of civil carnage to date, was closed. In 1854 the New York Mercantile Library moved into the former site and renamed it Clinton Hall. Map courtesy of NYPL digital collection

The Astor Langdon House and Surrounding Area

By all accounts the Langdon house which was directly across from the opera house received the greatest amount of damage. The militia was ordered to fire a volley over the heads of the crowd as warning without much effect. The crowd pressed upon the militia lines pummeling with stones and in some cases attempted to wrench away the muskets. Astor Place is approximately 49 feet wide between the property lines and because the crowd was packed so tightly it made it difficult to evacuate under fire resulting in large casualties.

The Springfield 1842 musket depicted below was originally a smoothbore .69 caliber weapon developed for the military later adopting a rifled bore for more accuracy and range. Wounds caused by this musket ball and the adoption of the mini ball were devastating during the Civil War and resulted in many amputations.

Eyewitness Accounts

Around this edifice, we saw, a vast crowd was gathered. On the stage the English actor Macready was trying to play the part of Macbeth, in which he was interrupted by hisses and hootings, and encouraged by the cheers of a large audience, who had crowded the house to sustain him. On the outside a mob was gathering, trying to force an entrance into the house, and throwing volleys of stones at the barricaded windows. In the house the police were arresting those who made the disturbance—outside they were driven back by volleys of paving stones.

Phillip None: May 11—

I walked up this morning to the field of battle, in Astor place. The Opera-House

presents a shocking spectacle, and the adjacent buildings are smashed with

bullet holes. Mrs. Langdon’s house looks as if had withstood a siege. Groups of

people were standing around, some justifying the interference of the military,

but a large proportion were savage as tigers with the smell of blood …

Sylvester L. Wiley: "We tried to get into Mrs Langdon's house, as we did not know how much he (one of the wounded men) was hurt. We knocked at the door, which was opened by a gentleman, who repulsed us as soon as he saw what we wanted. He closed the door as far as he could but the crowd pressed so he could not quite get it closed, he sang out for assistance, when three or four men came from the back door. One of whom, a policeman, I knew him by his star struck me over the head and knocked my hat off so that it fell in the hall. I called on the crowd to give way..."

Thomas J. Belvin a neighbor: "Wall Street broker George W. Gedney was trying to get home. The newlywed "was shot instantly dead, as he was standing inside the railing by the Langdon mansion. "

Left: The eyewitness accounts as reported by the Brookly Eagle

The Diary of William C. McReady May 1849

May 7th.-Rehearsed with

much care. Looked at some papers (N.Y.) sent to me. Received note from Silliman,

which I answered. Rested. Went to theatre, dressed .... would be a good

house, for there was-an unusual sight-a great crowd outside. My call came; I had

heard immense applause and three cheers for Mr. Clarke in Macduff. I smiled and

said to myself, "They mistake him for me." I went on-the greatest applause, as

it seemed, from the whole house. I bowed respectfully, repeatedly. It still kept

on. I bowed as it were emphatically (to coin an expression for a bow), rather

significantly that I was touched by such a demonstration; it continued. I

thought, "This is becoming too much." It did not cease, and I began to

distinguish howlings from the right corner of the parquette. Still, I thought,

it is only like the Western shriek-a climax of their applause. At length I

became sensible there was opposition, and that the prolongation of the applause

was the struggle against it; I then waited for its subsidence, but no cessation;

I at last walked forward to address them, intending to say-" I felt pain and

shame, which the intelligent and respectable must feel for their country's

reputation, and that I would instantly resign my engagement rather than

encounter such disgraceful conduct." They would not let me speak. They hung out

placards-" You have been proved a liar," etc.; flung a rotten egg close to me. I

pointed it to the audience and smiled with contempt, persisting in my endeavour

to be heard. I could not have been less than a quarter of an hour on the stage

altogether, with perfect sang-froid and good-humour, reposing in the

consciousness of my own truth. At last there was nothing for it, and I said " Go

on," and the play, Macbeth, proceeded in dumb show, I hurrying the players on.

Copper cents were thrown, some struck me, four or five eggs, a great many

apples, nearly-if not quite-a peck of potatoes, lemons, pieces of wood, a bottle

of asafoetida which splashed my own dress, smelling, of course, most horribly.

The first act, at least in my scenes, with these accompaniments, passed in dumb

show; I looking directly at these men as they committed these outrages, and no

way moved by them. Behind the scenes some attempted to exhibit sympathy, which I

received very loftily, observing, "My concern was for the disgrace such people

inflicted on the character of the country." The second act closed exactly in the

same way. I dressed for the third and went on; the tumult the same, the missiles

growing thicker. At last a chair was thrown from the gallery on the stage,

something heavy was thrown into the orchestra (a chair) which made the remaining

musicians move out. Another chair was hurled by the same man, whom I saw

deliberately throw it, then wrench up another, and throw it too-I bowed to the

audience, and going up to Mr. Chippendale, observed that I thought "I had quite

fulfilled my obligation to Messrs. Niblo and Hackett, and that I should now

remain no longer." I accordingly went down and undressed; Colden was there and

seemed to apprehend danger out of doors; I did not. However, I took my dirk, but

thinking it unworthy to carry it, threw it down again. Colden (who made too much

of it), Tallmadge, and Emmett walked home with me; there was no sign of any

attempt in the back street, but there was a crowd at the front door, which

Colden had not been able to penetrate, and which, the Chief of the Police

informed me afterwards, made the strongest efforts to break into the house.

Colden was with me and Ruggleston came and joined us. I was in the best spirits,

and we talked over what was to be done. Several things proposed, rejected, and

certain things decided on, but so hastily that when they were gone I perceived

the course was yet to be fixed on. A Mr. Bennettstranger-came, as he said, from

young Astor and other names of the first, he said, to say that this should be

resisted, and to convey to me the expression of their regret, etc. I was not

quite sure of my man. Gould came, when they were gone, in great distress, having

heard all from Duyckirck. Our conversation overturned the decision with Ruggles

and Colden. He gone, Mr. Monnitt, my landlord, and one of the heads of the

police called, to show me a deposition taken from one of the rioters who had

been captured, and who, because he cried very much, was set at liberty. I asked

leave to copy the deposition and I am about to do it, and I suppose shall have a

long night's writing. And this is my treatment! Being left alone, I begin to

feel more seriously the indignities put on me, and entertain ideas of not going

on the stage again. Pray God I may do what is right. I will try to do so. I

thank His goodness that I am safe and unharmed. Wrote to dearest Catherine. May

10th.-I went, gaily, I may say, to the theatre, and on my way, looking down

Astor Place, saw one of the Harlem cars on the railroad stop and discharge a

full load of policemen; there seemed to be others at the door of the theatre. I

observed to myself, "This is good precaution." I went to my dressing-room, and

proceeded with the evening's business. The hairdresser was very late and my

equanimity was disturbed. I was ruffled and nervous from fear of being late, but

soon composed myself. The managers were delaying the beginning, and I was

unwilling to be behind the exact hour. The play began; there was some applause

to Mr. Clarke (I write of what I could hear in my room below). I was called, and

at my cue went on with full assurance, confidence, and cheerfulness. My

reception was very enthusiastic, but I soon discovered that there was

opposition, though less numerously manned than on Monday. I went right on when I

found that it would not instantly be quelled, looking at the wretched creatures

in the parquette, who shook their fists violently at me, and called out to me in

savage fury. I laughed at them, pointing them out with my truncheon to the

police, who, I feared, were about to repeat the inertness of the previous

evening. A black board with white letters was leaned against the side of the

proscenium: "The friends of order will remain silent." This had some effect in

making the rioters more conspicuous. My first, second, third scenes passed over

rapidly and unheard; at the end of the fourth one of the officers gave a signal,

the police rushed in at the two sides of the parquette, closed in upon the

scoundrels occupying the centre seats and furiously vociferating and

gesticulating, and seemed to lift them or bundle them in a body out of the

centre of the house, amid the cheers of the audience. I was in the act of making

my exit with Lady Macbeth, and stopped to witness this clever manoeuvre, which,

like a coup de main, swept the place clear at once. As well as I can remember

the bombardment outside now began. Stones were hurled against the windows in

Eighth Street, smashing many; the work of destruction became then more

systematic; the volleys of stones flew without intermission, battering and

smashing all before them; the Gallery and Upper Gallery still kept up the din

within, aided by the crashing of glass and boarding without. The second act

passed, the noise and violence without increasing, the contest within becoming

feebler. Mr. Povey, as I was going to my raised seat in the banquet scene, caine

up to me and, in an undertone and much frightened, urged me to cut out some part

of the play and bring it to a close. I turned round upon him very sharply, and

said that "I had consented to do this thingto place myself here, and whatever

the consequence I must go through with it-it must be done; that I could not cut

out. The audience had paid for so much, and the law compelled me to give it;

they would have cause for riot if all were not properly done." I was angry, and

spoke very sharply to the above effect. The banquet scene was partially heard

and applauded. I went down to change my dress, the battering at the building,

doors, and windows growing, like the fiends at the Old Woman of Berkely's

burial, louder and louder. Water was running down fast from the ceiling to the

floor of my room and making a pool there. I inquired; the stones hurled in had

broken some of the pipes.

The

fourth act passed; louder and more fierce waxed the furious noises against the

building and from without; for whenever a missile did effectual mischief in its

discharge it was hailed with shouts outside; stones came in through the windows,

and one struck the chandelier; the audience removed for protection behind the

walls; the house was considerably thinned, gaps of unoccupied seats appearing in

the audience part. The fifth act was heard, and in the very spirit of resistance

I flung my whole soul into every word I uttered, acting my very best and

exciting the audience to a sympathy even with the glowing words of fiction,

whilst these dreadful deeds of real crime and outrage were roaring at intervals

in our ears and rising to madness all round us. The death of Macbeth was loudly

cheered, and on being lifted up and told that I was called, I went on, and, with

action earnestly and most emphatically expressive of my sympathy with them and

my feelings of gratefulness to them, I quitted the New York stage amid the

acclamations of those before me. Going to my room I began without loss of time

to undress, but with no feeling of fear or apprehension. When washed and half

dressed, persons came into my room-consternation on the faces of some; fear,

anxiety, and distress on those of others. "The mob were getting stronger; why

were not the military sent for? " "They were here." "Where? Why did they not

act?" "They were not here; they were drawn up in the Bowery." "Of what use were

they there?" Other arrivals. "The military had come upon the ground." "Why did

they not disperse the mob then? " These questions and answers, with many others,

were passed to and fro among the persons round me whilst I was finishing my

hasty toilet, I occasionally putting in a question or remark. Suddenly we heard

a volley of musketry: "Hark! what's that? " I asked. "The soldiers have fired."

"My God I " I exclaimed. Another volley, and another! The question among those

surrounding me (there were, that I remember, Ruggles, Judge Kent, D. Colden, R.

Emmett, a friend of his in some official station, Fry, Sefton, Chippendale, and

I think the performer who played Malcolm, etc.) was, which way was I to go out?

News came that several were killed; I was really insensible to the degree of

danger in which I stood, and saw at once-there being no avoidance-there was

nothing for it but to meet the worst with dignity, and so I stood prepared. They

sent some one to reconnoitre, and urged the necessity of a change in my

appearance. I was confident that people did not know my person, and repeated

this belief. They overbore all objections, and took the drab surtout of the

performer of Malcolm, he taking my black one; they insisted, too, that I must

not wear my hat; I said, "Very well; lend me a cap." Mr. Sefton gave me his,

which was cut all up the back to go upon my head. Thus equipped I went out,

following Robert Emmett to the stage door; here we were stopped, not being

allowed to pass. The "friend " was to follow us as a sort of aide, but we soon

lost him. We crossed the stage, descended into the orchestra, got over into the

parquette, and passing into the centre passage went along with the thin stream

of the audience moving out. We went right on, down the flight of stairs and out

of the door into Eighth Street. All was clear in front-kept so by two cordons or

lines of police at either end of the building stretched right across. We passed

the line near Broadway, and went on threading the excited crowd, twice or three

times muttering in Emmett's ear, "You are walking too fast." We crossed

Broadway, still through a scattered crowd, and walked on along Clinton Place

till we passed the street leading down to the New York Hotel. I then said, "Are

you going to your own house? " "Yes." We reached it, and having opened the door

with a latch-key, closing it after us, he said, "You are safe here; no one will

know anything about you; you shall have a bed in ten minutes or a quarter of an

hour, and you may depend upon all in this house." I sat down in the

drawing-room, talking of the facts about us, and wondering at myself and my

condition, secretly preparing myself for the worst result, viz., falling into

the hands of those sanguinary ruffians. A son of Emmett's was there, Robert; in

about a quarter of an hour Colden came in. Several men had been killed, how many

not certainly known yet. "You must leave the city at once; you must not stay

here!" It was then a consultation between these excellent friends, I-putting in

an occasional opinion objecting or suggesting upon the safest course to pursue.

At length it was decided, and Robert was sent out to find Richard, another son,

probably at the Racket Club, to put the plan in execution. He was met by Robert

in the street, and both returned with additional reports; the crowd was still

there, the excitement still active. Richard was sent to the livery stable to

order a carriage -and good pair of horses to be at Emmett's door at four o'clock

in the morning, "to take a doctor to some gentleman's house near New Rochelle."

This was done and well done by him; Colden and Emmett went out to.reconnoitre,

and they had, as I learned from Emmett, gone to the New York hotel, at the door

of which was still a knot of watchers, and to Emmett's inquiries told him, if

any threats were made, to allow a committee of the crowd to enter 1849 and

search the house for me. Emmett returned with my own hat, one from the hotel,

and I had got Colden's coat. An omnibus drove furiously down the street,

followed by a shouting crowd. We asked Richard, when he came in, what it was; he

said, " Merely an omnibus," but next morning he told me that he asked the men

pursuing, " What was the matter? " and one answered, "Macready's in that

omnibus; they've killed twenty of us, and by G- we'll kill him! " Well, all was

settled; it was believed that twenty had perished. Robert went to bed to his

wife. Emmett went up-stairs to lie down, which I declined to do, and with

Richard went down into the comfortable office below before a good fire and, by

the help of a cigar, to count the slow hours till four o'clock. We talked and he

dozed, and I listened to the sounds of the night, and thought of home, and what

would be the anguish of hearts there if I fell in this brutal outbreak; but I

resolved to do what was right

and becoming. The clock struck four; we were on

the move; Emmett came down; sent Richard to look after the carriage. All was

still in the dawn of morning, but we waited some ten minutes-an age of

suspense-the carriage arrived. I shook the hand of my preserver and friend-my

heart responded to my parting prayer of " God bless him "-and stepping into the

carriage, a covered phaeton, we turned up Fifth Avenue, and were on our way to

safety. Thank God. During some of the time of waiting I had felt depressed and

rather low, but I believe I showed no fear, and felt determined to do my duty,

whatever it might be, acting or suffering. We met onlymarket carts, butchers'

orgardeners', and labourers going to their early work; the morning was clear and

fresh, and the air was cooling to my forehead, hot and aching with want of

sleep. The scenery through which we passed, crossing the Manhattan, giving views

of the various inlets of the sound, diversified with gentlemen's seats, at any

other time would have excited an interest in me, now one's thought or series of

thoughts, with wanderings to home and my beloved ones, gave me no time for

passing objects. I thought as we passed Harlem Station, it would never have done

to have ventured there. Some of the places- on the road were familiar to my

recollection, having been known under happier circumstances.' May 15th.-Read the

telegraphic verdict on the killed: "That the deceased persons came to their

deaths by gun-shot wounds, the 1 In the following month of September ten of the

Astor Place rioters were tried at the Court of General Sessions, New York,

before Judge Daly and a jury, and after a trial of fifteen days were all

convicted. The sentences varied from one month's imprisonment to imprisonment

for one year and payment of a fine of $250-(note by Sir F. Poliock). guns being fired by the military, by order

of the civil authorities of New York, and that the authorities were justified,

under the existing circumstances, in ordering the military to fire upon the mob;

and we further believe that if a larger number of policemen had been ordered

out, the necessity of a resort to the use of the military might have been

avoided."

and becoming. The clock struck four; we were on

the move; Emmett came down; sent Richard to look after the carriage. All was

still in the dawn of morning, but we waited some ten minutes-an age of

suspense-the carriage arrived. I shook the hand of my preserver and friend-my

heart responded to my parting prayer of " God bless him "-and stepping into the

carriage, a covered phaeton, we turned up Fifth Avenue, and were on our way to

safety. Thank God. During some of the time of waiting I had felt depressed and

rather low, but I believe I showed no fear, and felt determined to do my duty,

whatever it might be, acting or suffering. We met onlymarket carts, butchers'

orgardeners', and labourers going to their early work; the morning was clear and

fresh, and the air was cooling to my forehead, hot and aching with want of

sleep. The scenery through which we passed, crossing the Manhattan, giving views

of the various inlets of the sound, diversified with gentlemen's seats, at any

other time would have excited an interest in me, now one's thought or series of

thoughts, with wanderings to home and my beloved ones, gave me no time for

passing objects. I thought as we passed Harlem Station, it would never have done

to have ventured there. Some of the places- on the road were familiar to my

recollection, having been known under happier circumstances.' May 15th.-Read the

telegraphic verdict on the killed: "That the deceased persons came to their

deaths by gun-shot wounds, the 1 In the following month of September ten of the

Astor Place rioters were tried at the Court of General Sessions, New York,

before Judge Daly and a jury, and after a trial of fifteen days were all

convicted. The sentences varied from one month's imprisonment to imprisonment

for one year and payment of a fine of $250-(note by Sir F. Poliock). guns being fired by the military, by order

of the civil authorities of New York, and that the authorities were justified,

under the existing circumstances, in ordering the military to fire upon the mob;

and we further believe that if a larger number of policemen had been ordered

out, the necessity of a resort to the use of the military might have been

avoided."

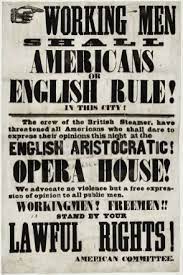

Above: Anti English Handbill

Edwin Forrest March 9, 1806- December 12, 1872

Edwin Forrest was one of America's most famous thespians born in Philadelphia in 1806. His mother was of German decent an his father was Scottish. From the very beginning his interest in drama led to a lifetime of theatrical fame. He is perhaps known for his portrayals of Shakespearian figures which thrilled American audiences for decades. However he will forever be known for his rivalry with English born actor William Macready and the events leading up to the riots which took place on May 10, 1849 surrounding the Astor Place Opera House.

At first Forrest and Macready were on friendly terms, with Macready even helping to advance the career of Forrest, but a misunderstanding between them would lead to the vitriol that would last for the rest of their professional lives. Forrest was also involved with a nasty and well published divorce with his wife Catherine Norton Sinclair that resulted in her winning a large settlement. Forrest was ordered to pay Catherine $3000 a month for the rest of her life. All his properties were subject to leans by the court to insure that the settlement was upheld.

In 1855 Edwin Forrest sold his home at 436 West 22nd street in New York and left permanently for Philadelphia. During that time he removed to a new mansion that was built at 1346 North Broad Street which would become his permanent residence thereafter.

The 1850 census to the left shows him living with his sisters.

The purpose

On April 1, 2022 the Department of Commerce of the United States

released the 1950 census in accordance with privacy laws dictated by the 72

year mandatory wait period (Public Law 95-416 95th Congress).

The census is required by Article 1 Section 2 of the United States

Constitution every ten years for the purpose of congressional apportionment.

.

Article 1, Section 2 of the United States

Constitution:

The actual Enumeration shall be made within

three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States,

and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall

by Law direct.

In addition to determining congressional seats, census figures have been

used to determine lifespan, immigration, occupation, personal wealth, and

state and local appropriations.

Questions Asked in 1950

Beginning with the 1940 census a separate

questionnaire was appended to the bottom of the census sheet.

Census questionnaires have changed over time.

From 1850 to 1950, six basic questions asked in each census remained the

same: name, age, gender, race, occupation, and place of birth.

Relationship to head of household was asked from 1880 to 1950, and the

citizenship status of each foreign-born person was asked from 1890 to 1950.

The nature and number of additional questions has changed over time. This

post will take a look at the major differences between the 1940 census and

the Form P1, 1950 Census of Population and Housing, that was

the standard fill-in-the-blank census form used in most of the continental

United States.

Name of street, avenue, or road

House and apartment number

Serial number of dwelling unit

Is this house on a farm or ranch?

Is this house on a place of three or more acres?

Agricultural Questionnaire Number

Name

Relationship to head of household

Race

Sex

Age on last birthday

Marital status: Married (Mar), Widowed (Wd), Divorced (D), or

Separated (Sep)

State or country of birth

Naturalization status if foreign born (Yes or NAT, No or Al, or AP

for born abroad of American parents)

Questions for persons fourteen years of age

and over

15. Was this person

working (Wk), unable to work (U), keeping house (H), or doing something else

(Ot) most of last week

If H or Ot in item 15: Did this person do any

work at all last week?

If No in item 16: Was this person looking for

work?

If No in item 17: Even though he didn’t work

last week, does he have a job or business?

If Wk in item 15 or Yes in item 16: How many

hours did he work last week?

a. Occupation

b. Industry in which person worked

c. Class of worker: Private employer (P), government (G), in his or her

own business (O), or without pay on family farm or business (NP)

The Difference Between the 1940 and 1950

Addendums

The questions on the standard 1940 and 1950

census forms were similar. The most significant differences between

them are the addendums:

·

In 1940, each census page had lines for 40 persons;

in 1950, this was reduced to 30 lines in order to ask “sample” questions of

more people and give the enumerator space to write notes and explanations if

they were needed.

·

In 1940, only two persons on each form answered

sample questions. In 1950, six people on each form were asked sample

questions, and the 6th person answered several additional sample questions.

·

In 1940, everyone was asked whether they had lived in

the same place, same county, or same state in 1935. In 1950, only

persons on six “sample” lines were asked what county and state (or foreign

country) they had lived in “a year ago” in 1949.

·

In 1940, everyone was asked the highest grade of

school they had attended and if they had attended school since March 1,

1940. In 1950, only persons on six “sample” lines were asked the

highest grade they had attended, whether they had completed that grade, and

whether they had attended school at any time since February 1, 1950.

·

In 1940, everyone age 14 or over were asked if they

had worked (or been assigned to work) on public emergency work for agencies

such as the Work Projects Administration (WPA), Civilian Conservation Corps

(CCC), and National Youth Administration (NYA) during the week of March

24-31, 1940. Those agencies were abolished during the 1940s so the question

was not asked in 1950.

·

In 1940, everyone age 14 or over was asked the dollar

amount of wages or salary income earned during calendar year 1939, and

whether they had received income of more than $50 from sources other than

wages or salary (yes/no). In 1950, only persons on six “sample” lines

were asked the dollar amount received in 1949 from wages or salary; working

in his or her own business, profession, or farm; or from interest,

dividends, veteran’s allowances, pensions, rents, or other non-wage or

non-salary income. In addition, persons on six “sample” lines were

asked how much money their relatives in the same household received from the

same sources. If the respondent was not comfortable answering these income

questions, the enumerator gave the person a form that could be directly

mailed to the Bureau of the Census. The enumerator was to record

“10,000+” for anyone who reported an amount more than $10,000.

(Average family income in 1950 was $3,300.)

·

In 1940, persons on two “sample” lines were asked if

they had a Social Security Number (SSN) and whether deductions had been made

from their wages or salary in 1939 for Old-Age Insurance or Railroad

Retirement. This was not asked in 1950. (Railroad works were exempt)

Source https://historyhub.history.gov/

Questions for persons on sample lines (six per

sheet)

Was he living in this same house a year ago?

Was he living on a farm a year ago?

Was he living in this same county a year ago?

If No in item 23: What county (24a) and state or

foreign country (24b) was he living in a year ago?

What country were his father and mother born in?

What is the highest grade of school that he has

attended?

Did he finish this grade?

Has he attended school at any time since February

1st? (Yes, No, or age 30 or over)

Questions for persons on sample lines fourteen

years of age and over (six per sheet)

If Yes in item 17: How many weeks has he been

looking for work?

Last year (1949), in how many weeks did this

person do any work (excluding work around the home)?

a. Last year (1949), how much money did he

earn working as an employee for wages or salary (before taxes and other

deductions)?

b. Last year (1949), how much money did he earn working in his own business,

professional practice, or farm (net income)?

c. Last year, how much money did he receive from interest, dividends,

veteran’s allowances, pensions, rents, or other income (excluding salary or

wages)?

a. Last year (1949), how much money did his

relatives in this household earn working for wages or salary (before taxes

and other deductions)?

b. Last year (1949), how much money did his relatives in this household earn

in their own business, professional practice, or farm (net income)?

c. Last year, how much money did his relatives in this household receive

from interest, dividends, veteran’s allowances, pensions, rents, or other

income (excluding salary or wages)?

If male, did he ever serve in the U.S. Armed

Forces during (33a) World War I, (33b) World War II, or (33c) any other time

including present service? (Yes/No).

To enumerator: If person worked last year (1

or more weeks in item 30): Is there any entry in items 20a, 20b, and 20c? If

Yes, skip to item 36. If No, make entries in items 35a, 35b, and 35c.

a. What kind of work did this person do in

his last (previous) job?

b. What kind of business or industry did he work in (in previous job)?

c. Class of worker (in previous job): Private employer (P), government (G),

in his or her own business (O), or without pay on family farm or business

(NP).

If ever married (Mar, Wd, D, or Sep in item

12): Has this person been married more than once? (Yes/No).

How many years since this person was (last)

married, widowed, divorced, or separated?

If female and ever married (Mar, Wd, D, or

Sep in item 12): How many children has she ever borne, not counting

stillbirths?

ED Numbers Explained

What is an Enumeration District EX: 31-266

(Five Points)

An enumeration district, as used by the Bureau of the

Census, was an area that could be covered by a single enumerator (census taker)

in one census period. Enumeration districts varied in size from a city block in

densely populated urban areas to an entire county in sparsely populated rural

areas.

What do the Enumeration District Numbers Mean

Enumeration Districts or ED’s as they are called,

are a set of numbers separated by a hyphen and followed by up to 4

numbers.

https://stevemorse.org/census/mcodes1950.htm

Ancestry has a great selection of phone directories

but it lacks a complete directory for Brooklyn NY. However there is

another free source that is available to genealogists that are searching for

family members in kings county NY.

Brooklyn And Manhattan,

Telephone Directories

In 1950 approximately 31 million households had a

telephone installed making it a valuable tool for locating family members.

If you are using Ancestry there are no directories for the years 1949 through

1952 and there are none for Brooklyn after 1933. While it is not unlikely

you will find what you are looking for there is a great deal of movement in the

postwar years. There are however other resources that you can use for your

1950 research.

The Brooklyn Public Library

https://archive.org/details/brooklynnewyorkc1950newy

U.S. Telephone Directory Collection, Available Online, 1950 | Library of

Congress (loc.gov)

I was looking for the descendants of Terence and

Elizabeth Duffy since Luke Duffy and wife Patricia are my godparents. I

knew they lived in Brooklyn but could not find them. The listing however

is under E. Duffy (Luke’s sister Evelyn)

One very successful method for locating family

members are obituary listings in newspapers, trade papers and church dedications

such as mass cards. I found this 1976 obituary in the local paper for

Patrick McCool and not only did I learn about his passing but his wife Johanna

as well. His parents Peter and Catherine (Kelly) are remembered we also

learned that he bought his farm in 1942 (the farm I remember).

Ancestry’s 1950 Census District Finder

The Ancestry ED locater is a good source for locating

family members in the 1950 census.

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/district-map/62308

But what if you don’t have a subscription?

The Morse Weintraub website is a stellar site filled with additional information

not only regarding the 1950 census but previous census years as well.

More on that below. The enumeration for Pine plains is seen below.

Notations

There are also many notations which on the 1950

census sheets (see above) which may be helpful in determining relationships.

The Morse Weintraub Census Website

This website is a goldmine of online information for

genealogists including US Census, Immigration and Passenger lists and State

Census images. Why are State Census Lists so important? Because in

some cases they are a link from the 1880 and 1900 US Census (the 1890 US Census

is not available).

https://stevemorse.org/census/unified.html

Census Codes Explained

https://stevemorse.org/census/codes.html

Beginning with the US Census of 1910, census takers

were instructed to use codes to further define gathered. In addition, in

1950 six additional lines of information were listed for lines 3, 8, 13, 18, 23,

and 28. These lines and codes are explained below.

John Duffy

Using the Morse/Weintraub codes to decipher columns B

through H

Column B: Birthplace if born outside US

US citizen

Ireland (Eire)